The Mozambique-born forward, who would have turned 80 on January 25, tore up the rule book of what a striker could be in the 1960s with Benfica and adopted country Portugal. The Game columnist Andy Murray recalls what made the Black Pearl so special and so adored…

Remembering Eusebio, the greatest footballer Africa has ever produced

Remembering Eusebio da Silva Ferreira

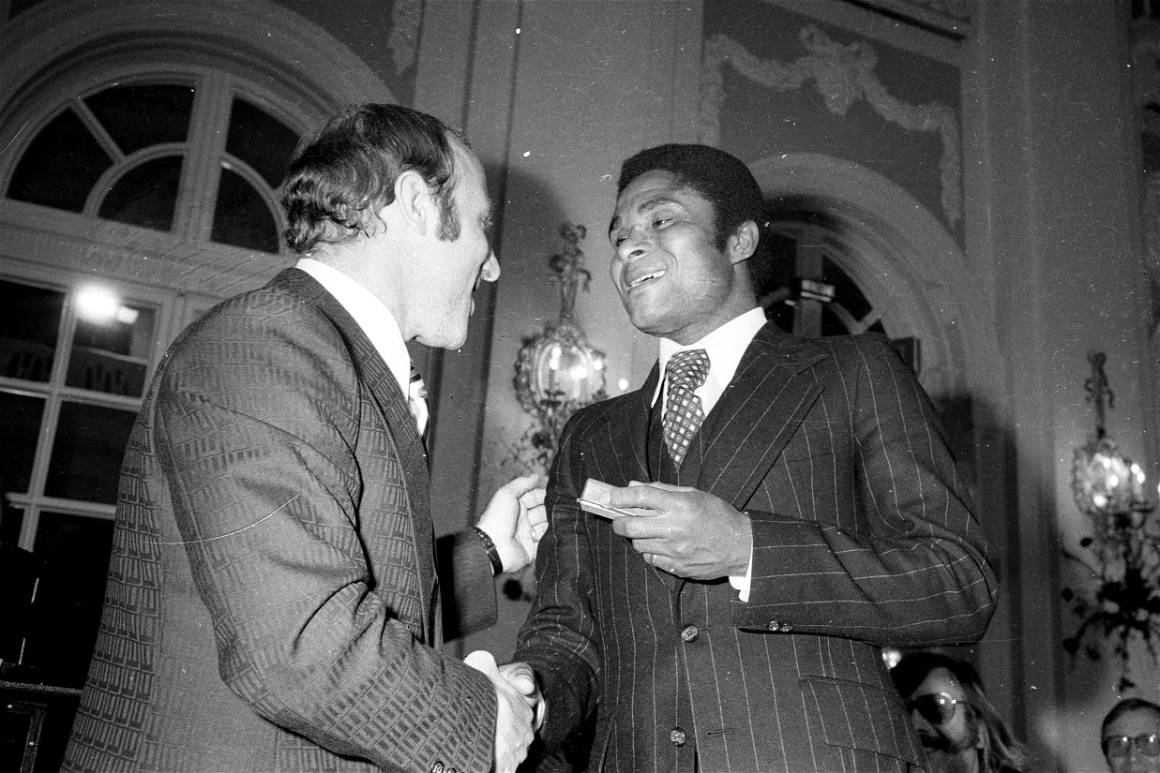

Bela Guttmann needed a haircut. It was October 1960 and Benfica’s manager, determined to rebuild the Portuguese champions from the bottom up despite winning the Primeira Liga title just four months earlier, had just sacked 20 first-team players. The Hungarian coach went to his local barber shop where he happened upon an old friend.

Jose Carlos Bauer was in town with touring Brazilian side Sao Paulo, one of the myriad teams Guttmann had managed in an already itinerant career. A first-team coach and noted talent spotter, Bauer waxed lyrical to Guttmann about an 18-year-old he’d seen play for Sporting Clube de Lourenco Marques, a feeder club for Lisbon giants Sporting, while on an earlier leg of their tour in Portuguese East Africa (present-day Mozambique). Bauer’s Sao Paulo overlords thought it too much of a risk to sign an inexperienced teenager from a Portuguese colony, even if he had scored a ludicrous 77 goals in 42 games and could already run the 100m in under 11 seconds.

A week later, Guttmann flew to Lourenco Marques (present-day Maputo) to see the prodigy for himself. Staggered by the youngster’s devastating eye for goal and leonine grace, Guttmann immediately cut a deal with the player’s mother for 250 contos [about €1,250 today], later doubled at her other son’s insistence. Benfica knew their bitter city rivals Sporting would be furious. During the transfer, the prodigy was codenamed ‘Ruth Masso’ to throw Sporting off the scent. When he finally arrived in Portugal on December 17, ‘Ruth’ was sent to Lagos, a small fishing village in the Algarve, while a legal challenge went through the courts. Eventually, the player was registered with Benfica in May 1961.

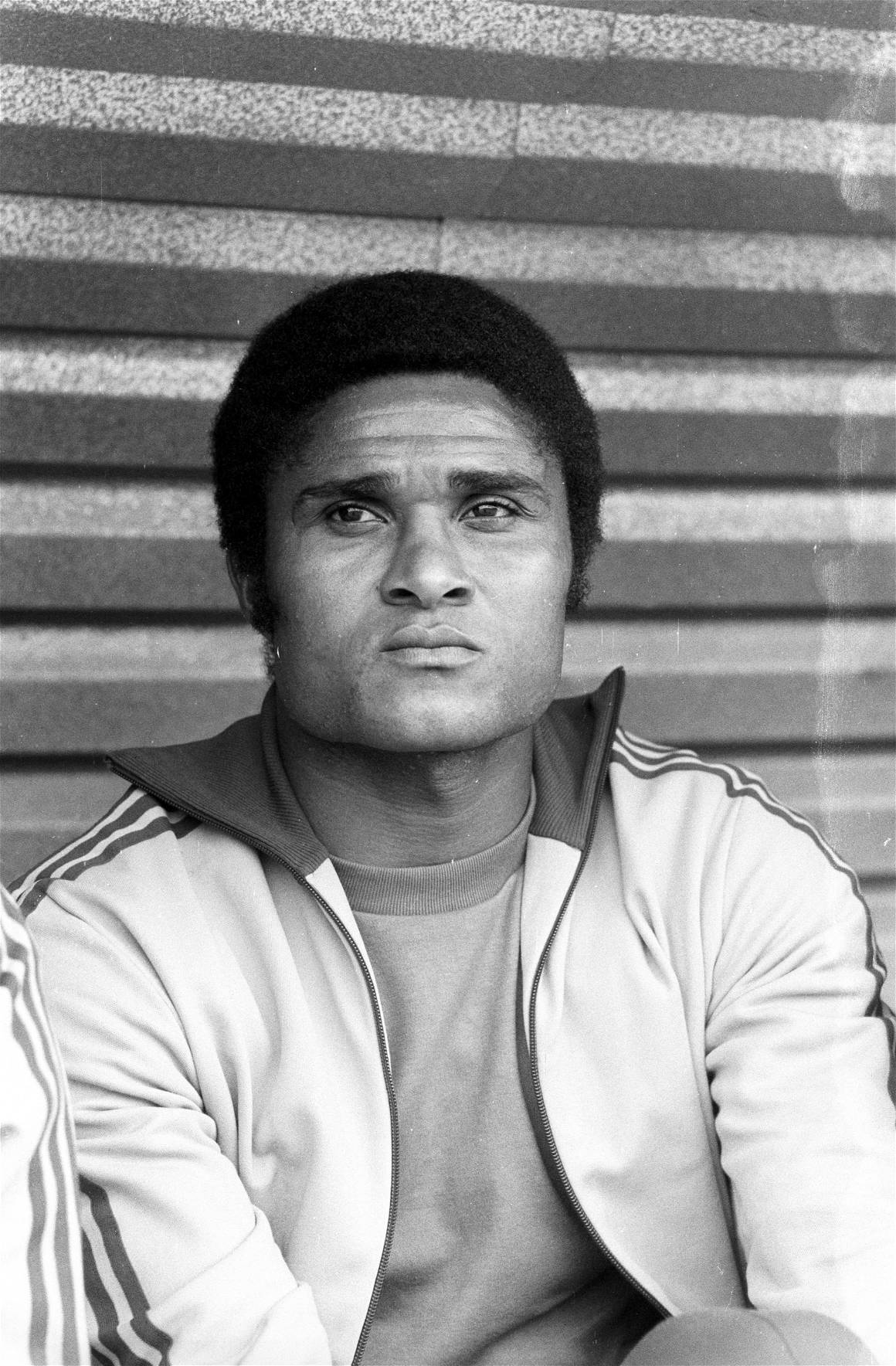

Eusebio da Silva Ferreira was worth every second’s effort. Standing at 5ft 9in with impossibly square shoulders and jawline, he had a middleweight boxer’s frame and a right-footed shot every bit as ferocious as a Sugar Ray Robinson hook. In an era when centre-forwards were conspicuous for what you might euphemistically call their efficiency of movement outside the penalty box, Eusebio was the complete package and a prototype for the multi-faceted strikers – think Didier Drogba, Robert Lewandowski and now Erling Haaland and Kylian Mbappe – which now dominate the elite. He could hold up the ball, was dominant in the air and was so skilful his dribbles left defenders dizzy and bruised in equal measure.

He was a goalscorer, too. Eusebio struck 727 times in 715 Benfica appearances, a record never to be matched, providing the end product which delivered 11 Primeira Liga titles, five Portuguese Cups and one European Cup. Mario Coluna, Jose Aguas, Antonio Simoes were central to the team of youngsters Guttmann built, but Eusebio was the jewel in the crown. His nickname the Black Pearl is troubling to modern ears, but at least half that moniker is supremely apt.

Born to a railroad worker Angolan father, who died when he was eight, and Mozambican housewife mother, Eusebio grew up in poverty in the backstreets of modern-day Maputo. Pretending to be Real Madrid star Alfredo Di Stefano, he regularly skipped school to play football barefoot with his friends, honing the technique that would eventually take him to Benfica.

After seeing his new signing train for the first time at the Stadium of Light – the latest African talent to be spirited from a colony for a relative pittance back to Portugal after Coluna, Matateu and Hilario – Eagles boss Guttmann shouted to his assistant Fernando Caiado, “It is gold. It is gold.” Jose Aguas, Benfica’s centre-forward and captain, was so staggered at his precocious team-mate’s talent he promptly suggested, “If it has to be me then so be it, but somebody has to drop out for him to play.”

On his debut in May 1961, Eusebio scored a hat-trick. His first official game came a week later in the third round of the Portuguese Cup against Vitoria de Setubal. Scheduled the day after Benfica had beaten Barcelona in the European Cup final, the Eagles played a reserve side, giving the newbie his chance. He scored again. Obviously.

A year later, the 19-year-old was lining up for defending champions Benfica against Real Madrid, and boyhood hero Di Stefano, in the 1962 European Cup Final. Eusebio’s two second-half goals secured a 5-3 win for Benfica. Ferenc Puskas, who scored a hat-trick that day for Madrid, swapped shirts with the matchwinner 18 years his junior, in a symbolic changing of the guard. By the end of the year, Eusebio finished second in the Ballon d’Or. In 1965, after firing nine in nine to take Benfica to a fourth European final in five years, he topped the vote for European football’s player of the year.

The following year, Eusebio took his unique gifts global for his adopted country, Portugal. Dictator Antonio Salazar was never going to pass up such an opportunity to exploit his colonies’ wealth on a football pitch as he had its cheap raw materials. Portugal had never come close to qualifying for a World Cup, but in 1966, they reached the semi-finals, thanks to Eusebio’s nine goals to win the Golden Boot. Two came against Pele’s Brazil, as Portugal’s rough-house tactics kicked O Rei off the pitch, much to a visibly angry Eusebio’s displeasure.

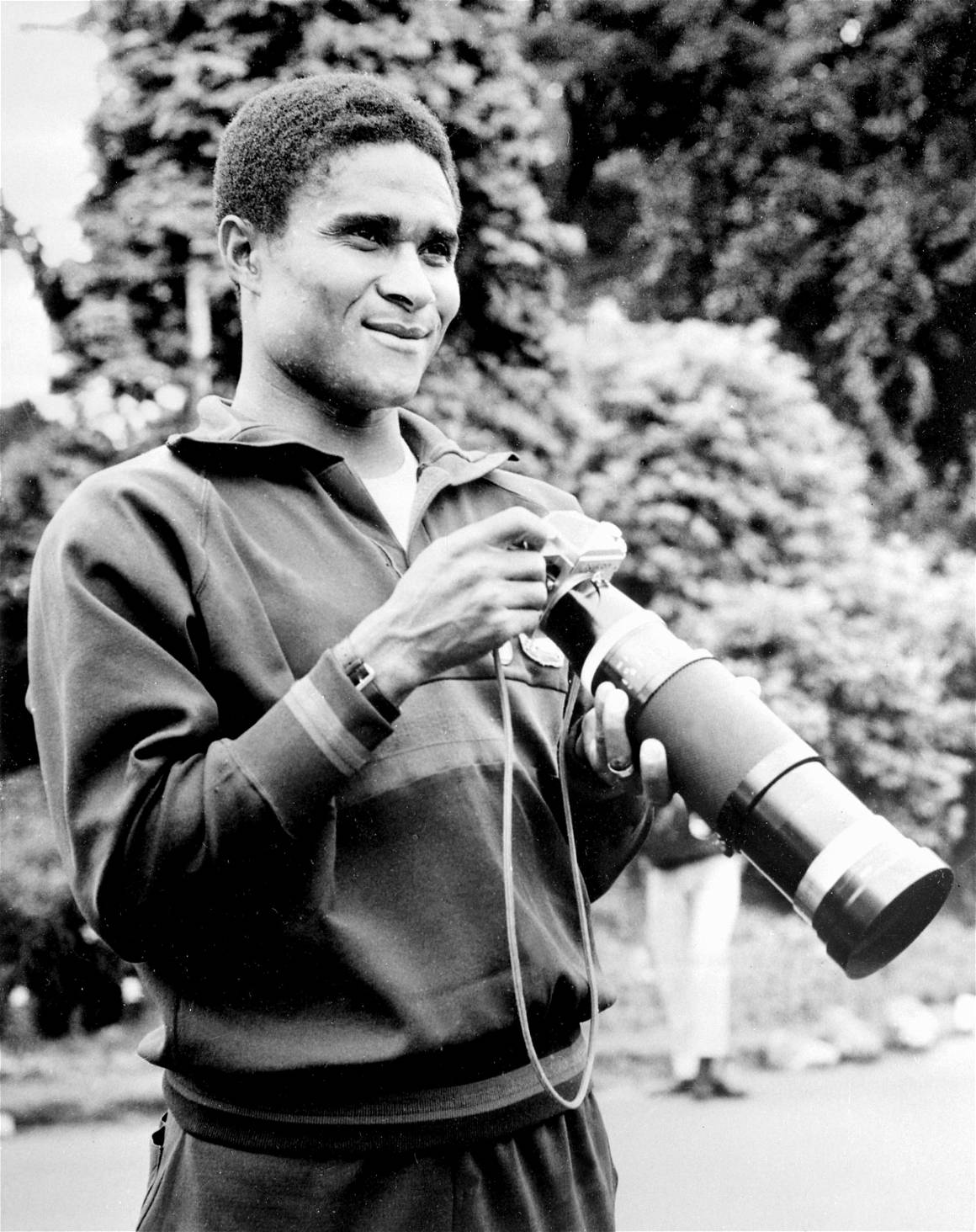

Three-nil down to North Korea in the quarter-finals, Eusebio – who spent much of his month in Blighty scouring record shops for Beatles LPs, and was later honoured with a Madame Tussauds waxwork – blasted four goals to take Portugal into the last four against hosts England. O Jogo das Lagrimas, the Game of Tears, ended with Eusebio inconsolable at full-time, the 2-1 defeat proving a nadir from which Portugal struggled to recover. They wouldn’t play another World Cup knockout game for 40 years.

Eusebio was in his prime. Only the personal intervention of dictator Salazar prevented a money-spinning transfer to Italian giants Inter Milan, who had beaten the striker’s Benfica in the 1965 European Cup Final. “No, you’re part of the patrimony of Portugal,” he was told. “You can’t leave.”

Yet he never bore a grudge. “I consider myself a citizen of the world but they didn’t see it that way,” Eusebio later told magazine FourFourTwo. “What’s amusing is that when I travel abroad with the presidents of Portugal, as I have done on occasion, nobody knows who they are in the street but everybody knows who I am. Benfica were the big winners because they always had Eusebio playing for them.”

Further Wembley heartbreak followed in 1968, as Benfica lost another European Cup final – Eusebio’s third – this time to Manchester United. In the last minute, the score locked at 1-1, the game’s pre-eminent striker had a gilt-edged chance to win Old Big Ears, but shot straight at United goalkeeper Alex Stepney. Eusebio immediately congratulated the keeper.

“I clapped Alex Stepney because it was a great save,” he recalled. “On and off the pitch I’m somebody who has always been a believer in fair play.” Benfica’s eventual 4-1 defeat after extra time was the bitterest pill to swallow in an otherwise storied career.

“It was a day which marked me forever,” he later recalled. “To miss that chance, right at the end… We would have won the European Cup. Instead it ended up being one of the blackest days in my life as a footballer. What I wouldn’t give to go back and play it again.”

He scored 50 goals in 1967/68, but the season marked the beginning of the end. Desperate to follow Sir Stanley Matthews and play into his 50s, Eusebio left Benfica in 1975 and wound down his days in the North American Soccer League, alongside Pele, at Boston Minutemen, Las Vegas Quicksilvers and Toronto Metros-Croatia among others, winning the league with the latter. He finally retired in 1979, aged 37, his knees shot after years of compensating for a bow-legged gait from his impoverished childhood.

For Portuguese football fans of a certain age, Eusebio – who would have turned 80 on January 25 – will forever be the country’s best footballer, regardless of Cristiano Ronaldo’s world-ruling modern brilliance and Euro 2016 triumph. Eusebio’s 41 goals in 64 international appearances may have all come for his adopted country, but this Titan of Mozambique is the greatest African-born player in history, a harbinger of what the future would hold for generations of centre-forwards.

“For me, Eusebio will always be the best player of all time,” Eusebio’s childhood hero Alfredo Di Stefano said shortly after the Black Pearl’s death in 2014.

Not bad for someone discovered in barbershop. Who knew having your hair cut could be so transformative?

Andy Murray is a sports writer and columnist for The Game. Check out some of his other articles with us that feature both in our mag and in our first zine issue FANsided.