From Alonso to Zidane, Allofs to Zoff, some of the biggest names have shone in the European Championships’ 64 years, but what of the lesser-heralded players, managers, fans and administrators? The Game Magazine columnist Andy Murray runs down some of the unsung heroes whose stories last the ages.

EUROs Unsung Heroes

EUROs Unsung Heroes by Andy Murray

Anyone with half a scintilla’s worth of football blood has savoured Marco van Basten’s ethereal EURO 88-winning volley on repeat for hundreds of hours. They will have luxuriated in Michel Platini almost winning the tournament single-handedly for France four years before that, scoring nine goals in just five matches, or Spain’s pass masters Xavi and Andres Iniesta passing their way to back-to-back titles in 2008 and 2012.

Yet EUROs history is littered with myriad lesser-known unsung heroes, whose stories resonate every bit as much as the big names, from goalkeeper extraordinaire Lev Yashin in the inaugural 1960 tournament to Giorgio Chiellini, whose all-timer foul on England’s Bukayo Saka in the pandemic-delayed EURO 2020 final three years ago sparked more memes than an adult should reasonably be expected to keep laughing at.

So, who should we really be celebrating? Who has changed the course of this quadrennial footballing jamboree through their own genius, force of will or undying fandom? Well, for starters, these 11 unsung heroes.

Henri Delaunay

Sure, the guy has a literal trophy named after him, but there would be no European Championships without the one-time referee who gave up officiating only after being struck in the face so severely by an errant ball that he swallowed his own whistle and broke two teeth. Deciding a career off the pitch was far less detrimental to his long-term health and ability to eat non-liquidised food; Delaunay hung up his whistle and set about an administrative revolution.

Delaunay became general secretary of the French Football Federation in 1919 and sat on the FIFA board from 1924 to 1928. The Parisian was determined to establish some sort of European equivalent to the World Cup, established by compatriot and FIFA president Jules Rimet in 1930 and first floated the idea as far back as 1927.

Elected as the first general secretary of European football’s governing body, UEFA, in June 1954, Delaunay remained in the role until his death the following November, aged 72. Succeeded by his son Pierre, Delaunay had already started the wheels in motion for the first European Championship in 1960, won by the Soviet Union.

Captain Igor Netto was the first player to get their hands on the Henri Delaunay Trophy, and his teammates headed out to a Paris café later that evening for a glass of wine. “We didn’t drink much,” said right-half Yuriy Voyonov. “We were drunk on victory.”

Jose Angel Iribar

You often hear that politics and sports should never mix, yet Iribar is the glorious alternative to such facile statements. A tree trunk of a man with the iron will to stand up for what he believed in, El Chopo (the Poplar) was Spain’s first-choice goalkeeper for more than a decade but was only 21 and with just two caps to his name when La Roja arrived at the EURO 64 finals.

Four years earlier, Spain had refused to play the Soviet Union in qualifying for the inaugural tournament. General Franco, under whose brutal right-wing dictatorship persecuted Spain’s rich regional individuality, feared the ramifications of losing to communism but, having seen the political capital gained by Nikita Khrushchev in 1960, decided the risk was worth taking.

A team of Basques, Catalans and Galicians triumphed 2-1 over the Soviets in the final, Marcelino – from Ares in Galicia – scoring the winner six minutes from time. Yet it was goalkeeper Iribar, producing typical athletic prodigies throughout, who realised in the celebrations that something felt amiss. The Athletic Bilbao goalkeeper, Basque born and bred and prevented from speaking his first language by dictatorial decree, realised that all the processions at the Prado royal palace back in Madrid were hollow.

“A few days passed, and we realised that if we’d lost, the situation would have been so different,” he said. Khrushchev was ousted in a Soviet coup inside four months. “It was a game we had to win at all costs, otherwise there would have been a hunt for culprits.”

Iribar never forgot. In the first Basque derby following Franco’s eventual death in 1975, the Athletic giant and Real Sociedad captain Inaxio Kortabarria together carried the still-illegal Ikurriña flag onto the pitch for its first public display in 36 years. It was, reported one journalist “a politically seminal act all Basques remember”.

El Chopo was a giant in more ways than one.

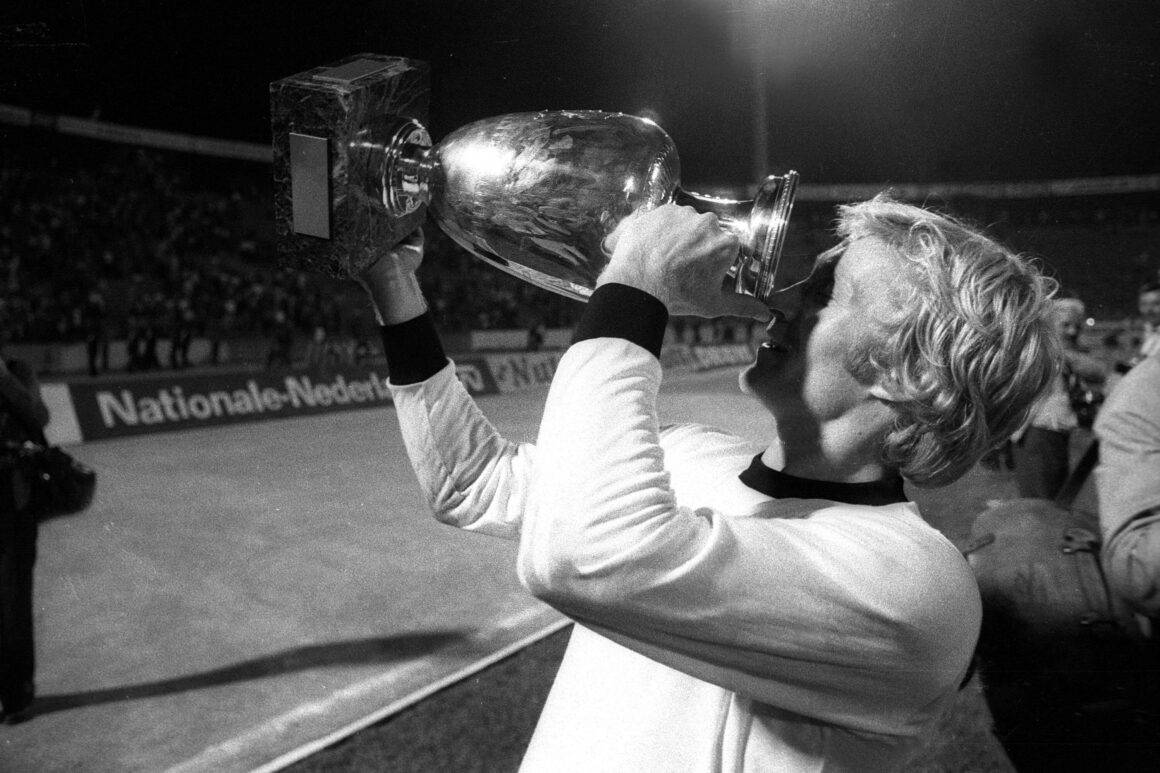

Herbert Wimmer

Every team, no matter how gifted or dusted with stars, needs a water carrier. At EURO 72, West Germany had one of the best to ever do the gig.

Nicknamed Iron Lung because of his unfathomable, almost impossible endurance, Wimmer was the perfect complement to the myriad attacking talents that existed around him. Gerd Müller was a penalty-box predator of rare compare, captain Franz Beckenbauer the smoothest of liberos who could turn defence into attack and Günter Netzer a long-haired playmaker so talented and unreal he seemed like Ziggy Stardust come from another planet.

Netzer, though, was also indolent to the point of stasis. Manager Helmut Schön knew this and picked Wimmer, Netzer’s club-mate, to perform the same role as he did for Borussia Mönchengladbach and do the running of two men. All high energy and lots of dirty work, Wimmer did it gladly, winning five Bundesligas and reaching the 1977 European Cup final.

The EURO 72 final, though, was the defensive midfielder’s destructive masterpiece. The West Germans 1-0 up against the Soviet Union, Wimmer made an uncharacteristic forward burst into the box, latching onto Jupp Heynckes’ through ball and firing low into the net with his left foot. The eventual 3-0 victory was a testament to the Germans’ dominance.

Beckenbauer, Müller and Netzer finished in the top three of the 1972 Ballon d’Or but none of that would have been possible without the attack dog who did all the dirty work for them.

Antonin Panenka

Slightly built but big of talent, Panenka was already a celebrated playmaker and creative type before he unleashed the moment that came to define both him and the penalty he’s since lent his name to (plus a respected football magazine in Spain). For two years, the dextrously skilled 27-year-old had been practising and perfecting a brand-new penalty away from prying eyes – using beer and chocolate as rewards for goalkeepers at Bohemians Prague who would help out – and now, in the EURO 76 final against defending champions West Germany, he gave it to the world.

Panenka had noticed that desperate to look active on their line, goalkeepers would always move when trying to save a penalty. Why not, he thought, just dink the ball, softly and delicately straight down the middle into the gap they vacate?

“For a goalkeeper, it is hard to stay in the middle because if he concedes a goal, he will always be blamed, [people will ask] why he has not even tried to get it,” he later recalled.

It had only been decided on the morning of the final that, in the event of a draw after 90 minutes and extra time, the result would be decided by a penalty shootout. Panenka resolved to play his trump card in the deciding kick – score and Czechoslovakia were European champions, miss and he’d face censure and probably worse back home from the local communist party.

“I suspect that he doesn’t like the sound of my name too much. I never wished to make him look ridiculous,” Panenka later said of the great Sepp Maier, who dove furiously out of the way, just as the Czech intended. “On the contrary, I chose the penalty because I saw and realised it was the easiest and simplest recipe for scoring a goal. It is a simple recipe.”

The Panenka was born and has enthralled those brave enough to try it ever since.

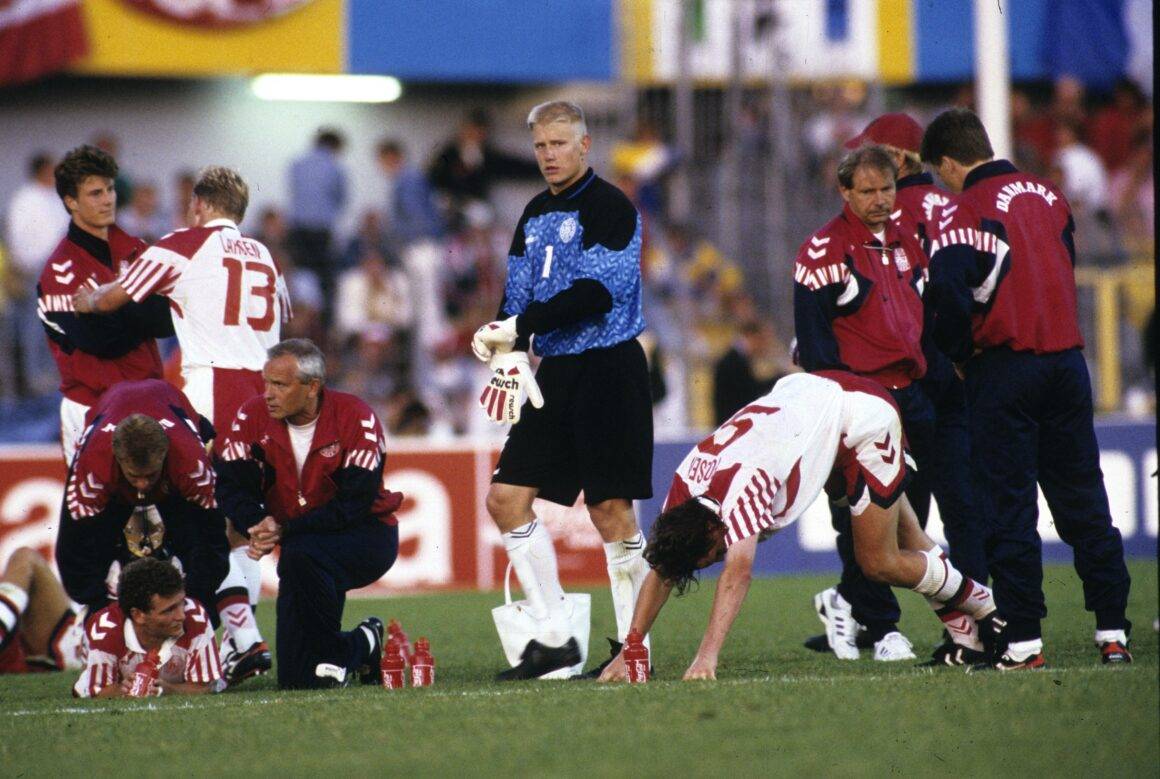

Richard Møller Nielsen

Denmark were literally on the beach when the squad suddenly got the call that Yugoslavia – descending into civil war and breaking up before the continent’s eyes – had been thrown out of EURO 92 and they were to take the defenestrated central Europeans’ place. That they didn’t just compete, but won the tournament having failed to qualify, remains arguably the finest story in the European Championships’ 64-year history.

Møller Nielsen produced alchemy, yet began the tournament as unpopular as it was possible to be. Assistant to the revered Sepp Piontek, who had led the Danish Dynamite as one of the most entertaining, cultish teams of the 1980s in reaching the EURO 84 semi-finals and last 16 of the 1986 World Cup, the manager couldn’t have been more different to his affable predecessor. Defensive, dour and obsessed with respect, Moller Nielsen had fallen out with Denmark’s best player, Michael Laudrup, who refused to play for him, while star goalkeeper Peter Schmeichel parped that while Piontek had made Danish football “upper class”, Nielsen had made it “lower class”.

With Denmark readmitted, Møller Nielsen tried to persuade the notoriously headstrong Laudrup out of retirement. He refused and watched his teammates – younger brother Brian included, who the manager had coaxed into playing – win the country’s only international tournament without him.

Working with a back five that shipped few chances in front, a goalkeeper in Schmeichel at the peak of his powers – the Manchester United gloveman was the semi-final shootout hero against the Dutch and saved from Stefan Reuter and Jurgen Klinsmann in the final – Møller Nielsen built a defensive shape that that few could breach. After failing to score in their opening two games against a limited England and France, the 150-1 outsiders came together under their under-fire coach to win an impossible triumph, Kim Vilfort’s final winner against Germany a cathartic explosion of grief and joy among Danes after it had leaked his daughter Line was dying of leukaemia. She died not long after witnessing her father’s finest moment.

Møller Nielsen had brought them all together. Not bad for a “lower class” coach and his ragtag squad fresh from the beach.

Baddiel, Skinner and the Lightning Seeds

The ultimate song about losing continues to elicit the rawest of emotions among England fans. The vast majority of Europe may choose not to believe it, but the “Football’s coming home” refrain is no reference to a nation drunk on its own success but England hosting a major tournament 30 years after the 1966 World Cup. Read the Three Lions lyrics – “30 years of hurt”, “all those oh so nears wear you down”, “England’s gonna blow it away” – and you’ll see they’re a study in fatalistic pessimism.

EURO 96 came at the right time for English football. After decades ravaged by hooliganism, the spectre of the 1989 Hillsborough stadium disaster and years of early exits for the national team, the late-90s came to define Cool Britania as the Britpop revolution of Blur and Oasis, political change and technological innovation restored good vibes. England needed an anthem.

Ian Broudie of Liverpool rock band the Lightning Seeds wrote the melody, complete with the catchy refrain he thought could become a terrace chant, and recruited comedians David Baddiel and Frank Skinner for the lyrics. Presenters of the wildly successful TV show Fantasy Football League, the duo threw themselves into a nostalgia wormhole and wrote a bittersweet love song to fandom. “Three Lions, really, is a song about magical thinking,” said Baddiel. “About assuming we are going to lose, reasonably, based on experience, but hoping that somehow we won’t.”

It caught the host nation’s mood and reached number one in the charts as the Three Lions reached a first semi-final in three decades. That they exited to Germany on penalties only served to prove the song’s central premise.

When England beat Scotland 2-0 in their second group game, the camera panned an exultant Wembley, having just seen Paul Gascoigne score the goal of the tournament. The song the FA themselves had commissioned was banned from being played but, suddenly, impossibly the opening bars hung in the north London air. “It’s coming home, it’s coming home…”

The camera found Baddiel and Skinner in the crowd, delirious with wonder at their song being sung back at them by 80,000 fans. In the bar afterwards, they met the Wembley stadium announcer who had defied his masters. “That wasn’t supposed to be played…” they told the announcer, a glint in his eye. “Yeah, but, y’know…” he replied.

It’s barely been off rotation since.

Roger Lemerre

Such was the luxurious quality at France’s disposal, nobody really noticed Roger Lemerre. Peak Zinedine Zidane, a rampant Thierry Henry, indefatigable Patrick Vieira and iconic leader Marcel Desailly. But the coach? Not so much.

Les Bleus had won their home 1998 World Cup under amiable boss Aime Jacquet but – not unreasonably – the avuncular manager decided that success could not be topped and stepped aside. Lemerre, Jacquet’s assistant, stepped up. He had to.

Zidane and Henry had never got on and seldom even passed to each other, yet the former’s wraithlike grace and latter’s scorching speed were France’s twin pillars. That Lemerre elicited a tune from both was extraordinary. It’s barely possible to play better than Zidane in the semi-final against Portugal, a symphony of flicks, tricks and golden goal penalty that sent Les Bleus through in extra time. Henry had scored a nerveless equaliser.

“This is a victory for attacking football,” Lemerre said. “I’m not going to pretend otherwise.”

In the final, Lemerre corralled his axis into further brilliance. Zidane and especially Henry superb throughout, only a last-second equaliser from substitute Sylvain Wiltord took France into extra time where David Trezeguet, another replacement, fired another golden goal winner to break Italian hearts. Lemerre’s attacking instincts again paid off.

“It is the willpower of the team that did it … The team wanted this trophy since the day it won the World Cup. We said that, if there was a second left, we had to go all out for it. The miracle happened and we caused it.”

You caused it, Roger. You did.

Angelos Charisteas

Even qualifying for EURO 2004 was an achievement for Greece. The Ethniki were appearing at just a third major tournament since 1930 with a record that read P6 W0 D1 L5 and were rankedk 150-1 outsiders for good reason. But, sometimes, the stars align and the impossible just happens.

Greece’s opening night 2-1 defeat of hosts Portugal could be written off as a one-off. Pat on the head, well done on your first finals victory and thanks for coming. You’ve had your fun; now kindly slink back off into obscurity. The big boys can take it from here.

Yet the upstarts had a taste for giant-killing. Centre-forward Charisteas was something of a giant himself. At 6ft 3in, he was slow, cumbersome but a menace in the air. He nearly fell over in scoring his opening goal of the tournament in the 1-1 draw against Spain that followed defeat of Portugal, but it was in the knockout stages that Charisteas came to life.

In the quarter-finals against France, the 24-year-old planted a ferocious header past Fabien Barthez to knock out the defending champions, was a general pest in the semi against the Czech Republic, then delivered his crowning moment.

Sure, Greece had beaten hosts Portugal on opening night, but it couldn’t happen again, not on 19-year-old Cristiano Ronaldo’s expected coronation as the world’s best young player. Instead, another towering Charisteas header – what else? – from Angelos Basinas’ corner delivered the goal that sealed the most improbable winners in history for Otto Rehhagel’s side. It was, Charisteas beamed at full-time, “a unique moment, which many of us may never experience again”.

He was right on both accounts. Greece (and Charisteas) soon reverted to the mean, scrabbling around unsuccessfully for qualifying points, but no one will forget that heady summer of love in Portugal when the beanpole forward turned into peak-Didier Drogba.

Manolo el del Bombo

You’ve probably never heard of Manuel Caceres Artesero, but you’ve definitely heard of his nickname. Manolo el del Bombo – Manolo the Bass Drum – is Spain’s most famous football fan, following la Roja home and away since the late 1970s and enlivening games everywhere with his percussive beat.

From the 1982 World Cup, in which he hitch-hiked around 15,800 km around Spain to follow his team, to the 2010 jamboree in South Africa he didn’t miss a game. Not one. Nada. Only a swift bout of pneumonia ensured he missed Spain’s quarter-final with Paraguay. For the final, Prince Felipe, heir to the throne and future Spanish king, invited him up to the royal box to celebrate Spain’s accession to the world summit.

Growing up in Huesca, the Valencia fan channelled his hometown’s love of percussion and began to take bass drums to games. He’s got through double figures over the years. He’s appeared in adverts, had his own bar and museum dedicated to fandom next to his beloved Mestalla, home to los Che, and only missed out on the 2018 World Cup in Russia in protest at his drum not being allowed with him.

Manolo isn’t hard to spot. He’s the guy dressed all in red, wearing a Spain shirt with the No12 on the back (to represent the fans being the 12th man) and a black beret to top off his signature look. At EURO 2008 and 2012, as Spain swept the board to become the only team to defend their European crown. The squad know him by name, each greeting him like a modern-day saint. The Spanish FA now pay for him to travel.

Manolo, then is the representation of the fan. “I lost everything for football: my family, my business, my money, the lot,” he once told The Guardian. “But I would do it all over again tomorrow. There is just nothing like representing your country.”

Gianluca Vialli

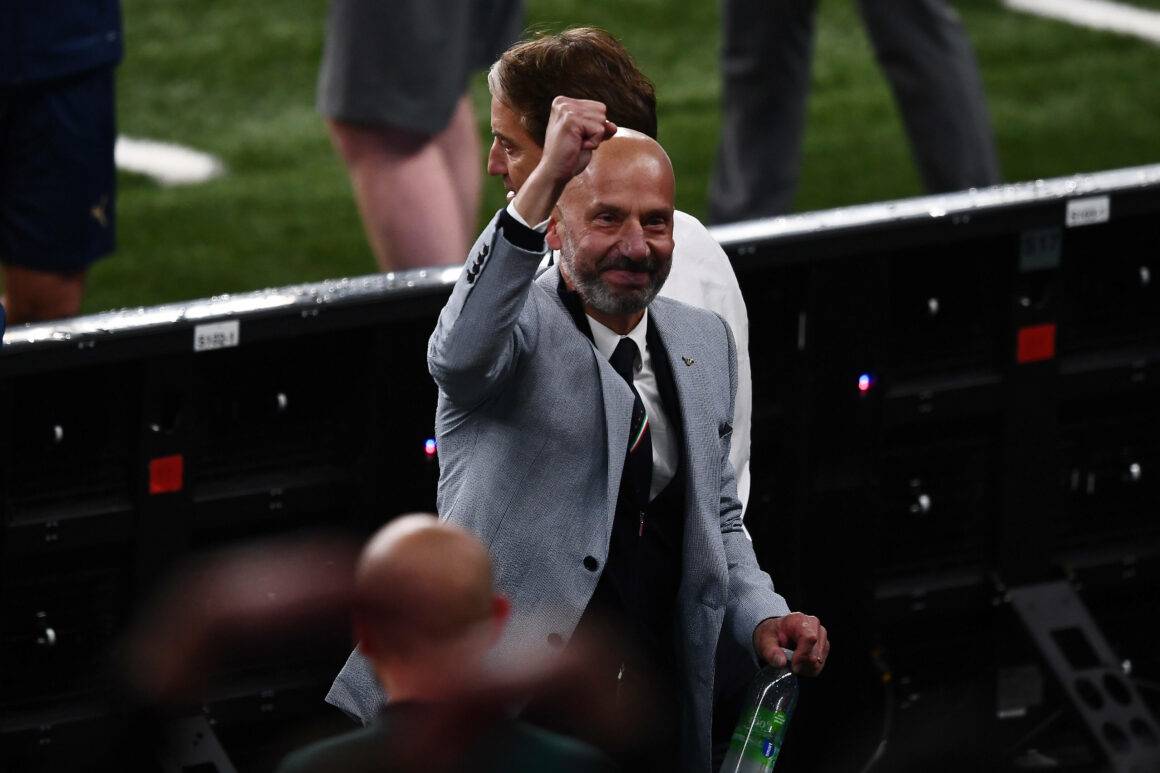

An hour and a half before Italy played England at Wembley in the EURO 2020 final, there was one man stood on the pitch, alone, taking in everything around him. It’s impossible to know if Gianluca Vialli knew then that the pancreatic cancer he had fought once, five years earlier, had returned – he announced it had five months later – but memories of the past European Cup and FA Cup finals he had played on that very pitch were sure to have come flooding back.

Vialli wasn’t a usual footballer. The son of a self-made millionaire, his was no rags-riches-tale but one of using his prodigious physical gifts to prove he warranted his spot first at local side Cremonese, then Sampdoria, Juventus and Chelsea. A powerful forward with a deadly eye for goal, he was the world’s most expensive football when moving to Juve but it was his jovial nature that endeared him to fans around the world.

Room-mates together at Sampdoria, Vialli and Roberto Mancini got the band back together when the latter took the Italy job in October 2019. Mancini knew he needed someone outgoing and jovial to soften some of his own manic intensity, so brought in his best friend of three decades as new delegation chief, a position unoccupied since the retirement of Italian great Gigi Riva.

The squad, predictably, loved him. Having gone through round after round of chemotherapy, Vialli was at pains to enjoy every moment, an attitude that rubbed off onto the squad. He was no assistant coach, more a motivator, a cajoler and provider of a comforting ear.

“I am not a warrior. I am not fighting cancer: it’s too strong an enemy and I would not stand a chance,” he wrote in his autobiography. “My goal is to keep walking, keep moving until he’s had enough and leaves me alone.”

Before Italy’s opening match of the tournament against Turkey, Vialli nearly missed the team bus from the hotel, much to everyone’s amusement. Italy won 3-0 and a superstition was born. For the remainder of the competition, the bus would start to move without him, with the follicly challenged former forward running out of the team hotel begging it to be stopped.

Before the final against England, the other country of his heart where he’d retired as a player to become Chelsea and where he’d met his wife Cathryn and had two daughters, Olivia and Sofia, Vialli read out a speech from former US president Theodore Roosevelt, which ended: “If he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.”

After Italy beat England on penalties to become European champions, there was only one person the squad wanted to talk about.

“He will hate me for saying this, but I don’t care,” right-back Alessandro Florenzi said immediately afterwards. “Everybody needs to know this. We have among us an example that teaches us how to live, in any moment, in any situation. And I’m talking about Gianluca Vialli, for us, he’s special. Without him, and without Mancini and the other coaches, this victory would mean nothing. He is a living example. I know he’ll get angry, but I just had to say it.”

The picture of an embracing Vialli and Mancini, each overcome by emotion, became the defining image of the final for many Italians. Hope triumphed adversity. Tragically, five months later, in December 2021, Vialli announced his cancer had returned and he died on January 6, 2023.

Few are the people in football about whom no one has a bad word to say. Gianluca Vialli was that man. He didn’t kick a ball at EURO 2020, but an Azzurri victory was impossible without him.