For Pride Month, we take a look back at our city’s longstanding roots in the LGBTQI+ movement, with archives of the queer haven that was 1920’s Berlin.

Before the terror, there was glitter: The queer haven that was 1920’s Berlin

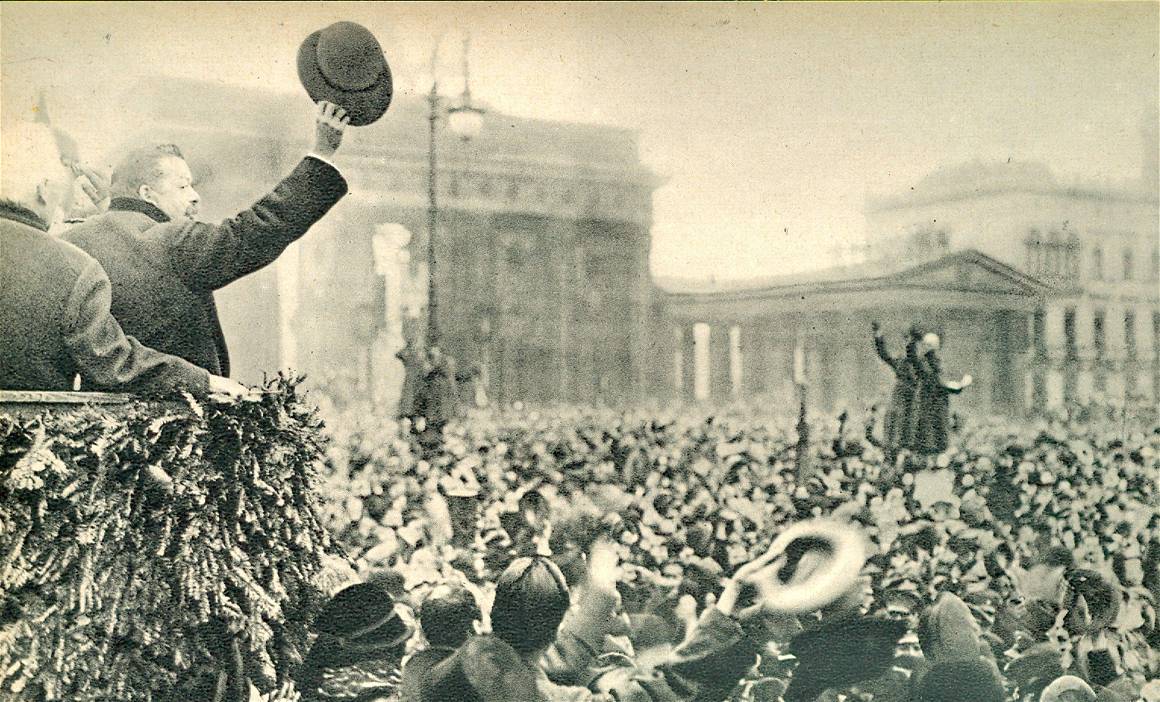

It is hard to believe that just before a man with a tiny mustache ruined all the fun, 1920’s Berlin was a queer haven. In fact, the first ever gay demonstration started in Berlin in 1922, and the Reichstag almost decriminalized homosexuality in 1929. Just before Germany threw itself into a sociopolitical storm of terror and then World War II, the capital was a cultural epicenter for a thriving queer community, constantly at odds with the city’s looming dark days ahead.

The Weimar Republic, Germany’s first parliamentary democracy lasted from 1918 until 1933 and was a time of progressive cultural renaissance from cinema, theater and music, to sexual liberation and a flourishing LGBTQI+ scene. Short-lived, the golden years were interrupted as the Nazis took over with homophobia high up on the agenda. The community suffered during this time, but its longstanding roots allowed it to come out stronger as Berlin remains to be a booming queer capital still today.

Already in 1897, Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld formed the Scientific Humanitarian Committee, a pioneer in the emancipation of oppressed groups, predominantly the queer community, and became one of the most politically influential associations until the early 1930’s. He later opened the Institute for Sexual Science in 1919, considered the first gay clinic and acted as a center for homosexual emancipation unwaveringly. Being jewish, he was particularly targeted and his clinic was later closed and looted by you-know-who. Its monument today sits opposite the Federal Chancellery. Hirschfeld’s counterpart Adolf Brand, opened the Association for Male Culture in 1900 which conjured a homoerotic cultural history, contributing to the popular avant-garde movement sweeping Europe at the time.

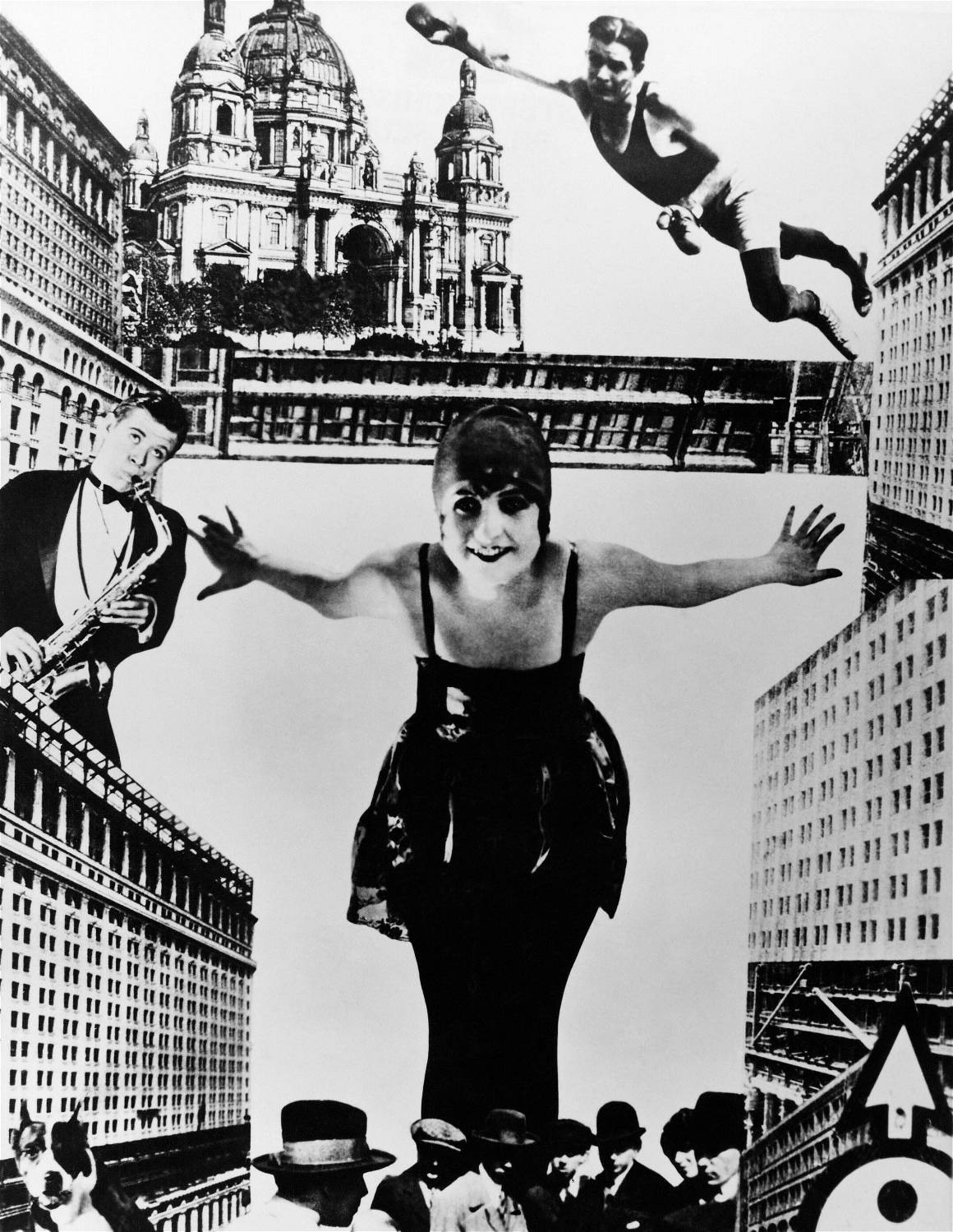

As the roaring twenties took off, Berlin was already home to around 40 known queer bars, a number which had doubled by 1925. Sexual liberation, especially for women and queers, was trending, dipping its toes into every cultural and social outlet. Still today, the city’s venues such as the Friedrichstadt-Palast, regularly put on shows emulating the 1920’s style.

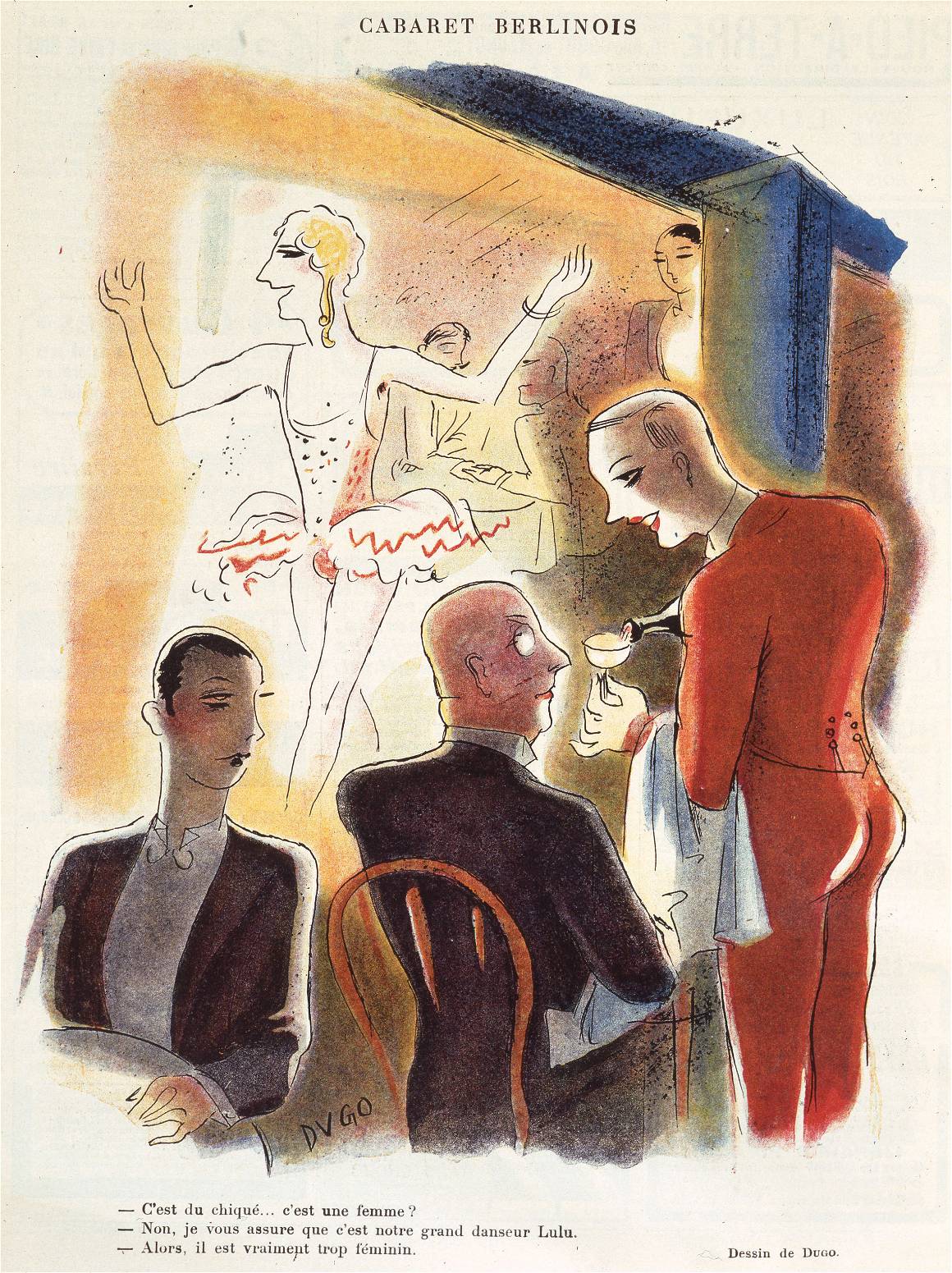

The cabaret bars and clubs like Eldorado were packed to the brim with lust, tassels, glitter and flamboyance. Drag shows were the norm and stars like Marlene Dietrich (a Berlin-native) and Josephine Baker who were icons for the queer community, performed regularly in Berlin’s lavish halls. Kiosks sold an array of well known queer publications like Die Hoffnung (The Hope), Blätter für Menschenrecht (Leaflets for Human Rights), Frauenliebe (Woman Love), and Das dritte Geschlecht (The Third Sex).

Austrian filmmaker Richard Oswald directed the world’s first known pro-gay film called Anders als die Andern (Unlike the Others) which premiered in Berlin’s Apollo Theater in 1919, swiftly sparking controversy and later banned in 1920. Going on to produce Gesetze der Liebe (Laws of Love) as an adaptation of Unlike the Others which was also banned, a copy made its way to Ukraine and was discovered by the Munich City Museum in the 1970’s.

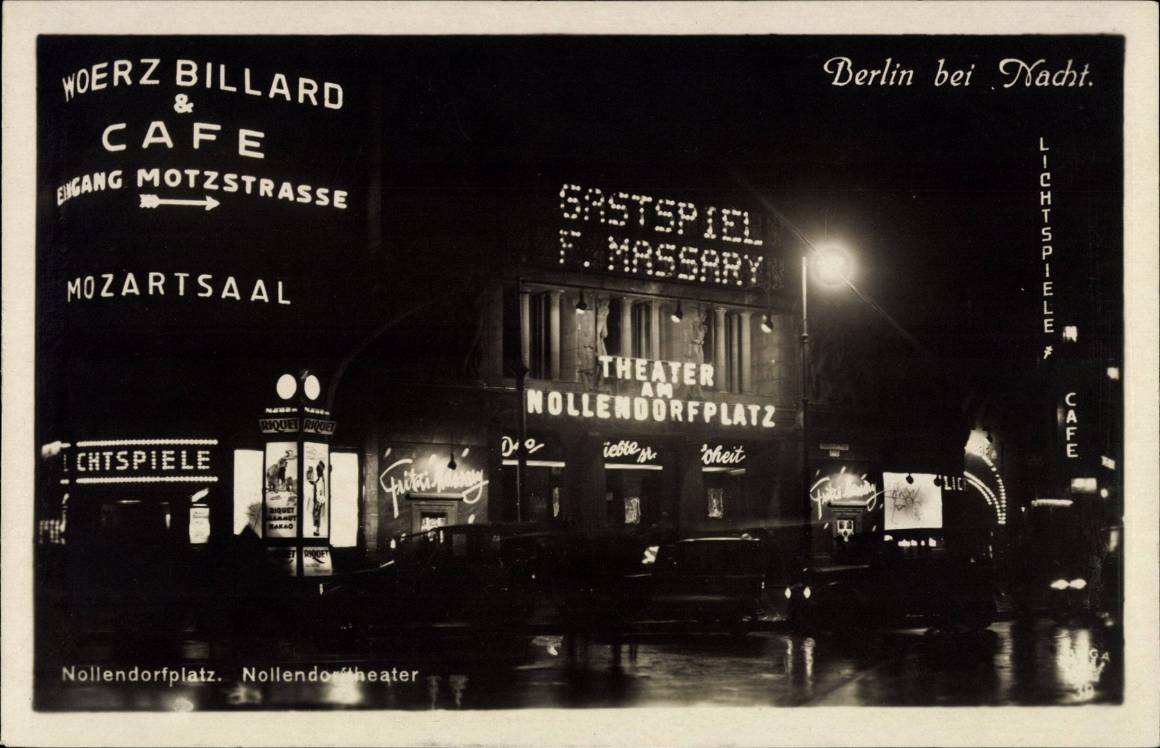

As homosexuality was still illegal, Berlin’s Tiergarten and other parks, Nollendorferplatz as well as train stations and the infamous octagonal public bathrooms, were well known meeting points for gay men throughout the early 20th century. Underground spaces flourished and Berlin became a queer capital – a reputation which survived the tragic Nazi crackdown and the Cold War.

As Hitler came to power, not only was their violent persecution, but bars and social-spaces were closed down along with human rights associations, queer publications and sexual health centers, accompanied by a harsh targeting of activists, artists, politicians and figures who supported the movement.

Homosexuality remained illegal until the late 1960’s so a lot of aspects of queer life were hidden from the mainstream, and few had the keys to the queer and underground castle, or a camera for that matter.

We’re celebrating the history of our city and those who fought to keep the community together, safe and seen. Discover some photography from our archives and look back on what was known as Berlin’s golden years.