Argentina’s captain led his country to a third World Cup at Qatar 2022, emulating his compatriot Diego Maradona’s singular genius 36 years earlier. The Game columnist Andy Murray explores what Messi’s triumph means for his legacy.

How Lionel Messi Became the GOAT

It didn’t even matter; it wasn’t the real World Cup

Lionel Messi had dreamt of this moment for more than three decades and presented the one trophy he truly coveted to his adoring Argentina fans, the smile impossible to wipe from his face. Yet the slab of metal Messi had been fondling, caressing and parading on his team’s lap of honour after beating France on penalties in the final of Qatar 2022 wasn’t that which he’d lifted in the official presentation earlier that evening.

It took Angel Di Maria, who had been posing with the real thing in the centre circle before giving it back to FIFA for safe keeping, to explain to Messi that the trophy in his arms was, in fact, a carefully made replica – weighing the same as the original and merely gold-plated – and owned by two fans in the crowd who had passed onto the players to celebrate. Di Maria and Messi shared a joke, signed the ‘alternative’ trophy and handed it back to the owners, Paula Zuzulich and her husband Manuel Zaro, in the crowd.

What mattered to Messi wasn’t the trophy’s authenticity – the fake featured in the most-liked post in Instagram history when the No.10 uploaded it hours late – but what it represented. The 35-year-old had won 11 domestic league titles, four Champions League, seven Ballons d’Or and even the Copa America – a first major title for his country – but now he had completed the set. Finally, after 16 years of trying, he was a world champion at the fifth attempt. The unbridled ecstasy etched across his face, real trophy or not, confirmed what his words never could.

I’ve interviewed Messi twice before, once in the build-up to the 2010 World Cup and again four years later. On both occasions, he was quiet and unwilling to part with much in the way of interest. Though it was clear winning a World Cup was top of his priorities, there was also a sense that he felt weighed down by the necessity to do so. The Albiceleste had Aguero, Di Maria, Javier Mascherano, Gonzalo Higuain and more top talent in their squad, yet they all looked to one player for inspiration.

“We know he is our main player, our captain, the best player in the world,” right-back Pablo Zabaleta said during the 2014 run to the final, where Argentina lost to Germany after extra-time. “We are so lucky to have Messi for Argentina. Every time we recover the ball, we try to find Messi as he’s the best player in the team, and he’ll score goals.” In short, ‘here you go, Leo, now go and do something brilliant’.

The pressure he felt was all-consuming, not least because he was battling against part of his own country. For years, a small but vocal section of Argentina doubted whether Messi had the requisite desire to play for La Seleccion, given the family’s decision to leave native Rosario for Barcelona when Leo was 13. Street urchins like Carlos Tevez, even Aguero, represented the Argentine people in a way some felt Messi never could, having spent so long living abroad.

Yet his desire to achieve for his homeland has never been in doubt. He has never lost his thick Rosarino accent; his diet has steadfastly remained the Argentinian staple of meat, meat, meat – his go-to dish is a milanesa, beef covered in breadcrumbs in his mother’s tomato sauce and slathered in cheese – and wife Antonella is also from his hometown. He only left because he had no option if he was going to become a footballer.

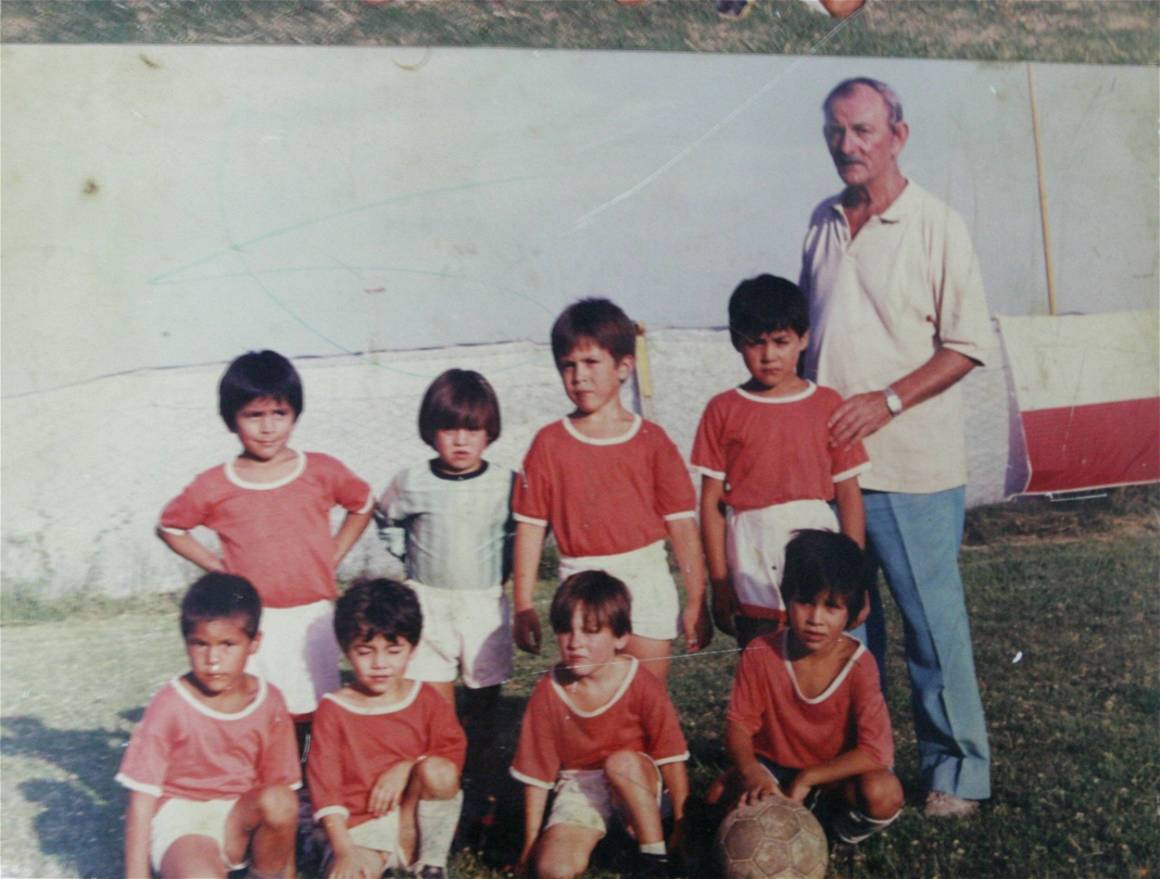

By the age of 10, as rumours about his preternatural gifts abounded at hometown club Newell’s Old Boys, he measured just 4ft 2in, impossibly small to become a professional.

“Some people around the football club came and told me: ‘We have this little lad. He’s a phenomenon, but he needs to grow,’” Dr. Diego Schwarzstein later said. “He was missing a hormone, which we can genetically recreate and give the body precisely what it is lacking. The only problem – it’s expensive.” Was it ever. Dr. Schwarzstein’s growth hormone costs $1,800 every two months. Jorge’s social security could cover the first few payments, but it would be unsustainable in the long-term. Depending on who you believe, Newell’s either couldn’t or wouldn’t pay.

Only Barcelona would stump up the cash when club scout Charly Rexach went over the heads of some directors – one huffing, “this kid would barely make a table footballer, never mind a Barça first-team player” – to improvise a contract on the back of a napkin. The Catalan club would pay for the necessary growth hormone, which Messi injected himself with every night. In three years, he grew nearly a foot and put on close to 4st in weight.

Yet, partly because of the disconnect between his stunning success halfway around the world and the shoulder-sagging struggles Messi had in an Argentina shirt – the red card he received seconds into his debut against Hungary a sign of things to come – it took his retirement for the country to realise what they were about to lose. When Messi lost a third major final in as many years at the 2016 Copa America – having broken Gabriel Batistuta’s national record of 54 goals for Argentina – he’d had enough. The pain of defeat, the implication he didn’t care enough, was too much to bear any longer.

“I tried my hardest,” he said post-game, that thick Rosarino accent cutting through the tears as he retired from international football. “The team has ended for me, a decision made.” Finally, Argentina realised what they’d lost. When the team arrived back in Buenos Aires, the squad was greeted with placard-waving fans writing, “don’t go, Leo”. A statue was unveiled in the capital to try to persuade him to continue. “Lionel Messi is the greatest thing we have in Argentina, and we must take care of him,” pleaded the country’s president Mauricio Macri.

After 46 days, Messi reversed his decision, confirming “my love for my country and this shirt is too great” not to continue in international exile. “Until I have some breath, I will keep trying to fulfil my dream, to win a title with Argentina,” he said. More hurt followed, but what the limp 2018 World Cup exit did achieve was the appreciation of a need for change.

When Lionel Scaloni took charge in August 2018, it was only ever supposed to be a stopgap. The former Deportivo La Coruña defender was just 40 and had only recently taken charge of Argentina’s Under-20s but agreed to temporarily take charge of the team. He soon earned key players’ trust by taking on the country’s FA to improve standards, persuaded Messi to trust him to turn things around and, crucially, called him “the best player of all time”.

Instead of asking Messi to just try and be brilliant, Scaloni built a team around his star – functional, yes, but with Rodrigo De Paul as midfield protector and a back three to allow Messi total creative freedom. The team he built has been called La Scaloneta in his honour.

Though Argentina lost to Brazil in the 2019 Copa America semi-finals, Messi felt included as a father figure shaping a young squad which in term looked up to him as part-leader, part-deity. When he’d ‘retired’ Messi received a letter from a 15-year-old kid from the San Martin district of Buenos Aires, beginning him not to retire. “We don’t deserve you,” wrote the youngster. Now, midfielder schemer Enzo Fernandez was Messi’s team-mate.

Scaloni also encouraged Messi to be nasty – fighting his corner against referees, speaking his mind to the FA and joins in with fan chants with the rest of the squad. By the 2021 Copa America, it all came together for Argentina to win their first major senior honour (excluding the Olympic gold in 2008 when Messi and the U23s emerged victorious) in 28 years. Messi scored four and laid on a further five assists.

Winning for Messi had become a driving force. “He suffered so much,” goalkeeper Emi Martinez said. “We wanted to win for Argentina, but we also wanted to win for him.” In Qatar, they did.

An almost impossible opening game defeat to Saudi Arabia effectively turned Argentina’s campaign into six consecutive knockout matches – lose any and they were out. He scored the opener against Mexico to restore a country’s confidence, then squared up to Aziz Behich at a throw-in in the last 16 against Australia to boost his adrenaline and repeated the trick. He scored in the penalty shootout win over the Netherlands in the quarter-final, then endeared himself to the nation yet further by shouting “¿qué miras, bobo?” (“what are you looking at, stupid?”) at passing Dutch forward Wout Weghorst while being interviewed live on air. In the last four, he twisted Croatia’s hitherto superb young defender Josko Gvardiol’s blood to set up Julian Alvarez having already scored himself.

In the final, he exorcised the demons of 2014 with another bewitching display featuring two goals and a penalty in the shootout. While his eternal rival Cristiano Ronaldo had departed the tournament in a swirl of his own hubris, unable to accept his diminishing powers like a footballing King Canute, Messi limited himself to bursts of brilliance. Those bursts, and his Argentina team-mates’ willing subjugation to the cause, were enough to achieve his immortality at his fifth and final World Cup.

For years the living ghost of Diego Maradona had weighed heavily on his psyche, the whole of Argentina expecting Messi to single-handedly lead a functional side to become world champions, as his predecessor had done in 1986. El Pibe de Oro had even been Messi’s coach in 2010, so omnipotent was he. At the first World Cup since Maradona’s death in November 2020, Messi set his own narrative. Streets have already been named after him, thousands of kids called Lionel or Lionela due to be born on September 18, 2023.

Raising that trophy to the fans, whether it was the real one or not, was symbolic. Sergio Aguero, the man on whose shoulders Messi had been hoisted on that lap of honour, had retired from football a little more than 12 months earlier because of a heart defect but returned as a member of the backroom team in Qatar, primarily to act as the Argentina captain’s room-mate. The pair again shared a room, drinking mate and reminiscing like it was 2005 and the U20 World Cup again. Two best friends who just happened to be among the planet’s finest footballers, celebrating each other’s destiny.

Messi’s destiny had been outlined from the very beginning. “When I first watched the videos, it was like seeing the light,” says Barcelona scout and agent Josep Maria Minguella, who played a major role in getting Messi to the Catalan capital for his trial in September 2000. “I reckon Leo comes from a marvellous planet, the one where exceptional people like violinists, architects and doctors are created. The chosen people.”

Messi now exists with Mozart, Gaudi and Jenner in the pantheon of singular geniuses who transcend their discipline. There could never be another Lionel Andrés Messi. Enjoy the GOAT while you can; he won’t be around forever.

More articles of Andy Murray:

World Cup 2022: The untold stories by Andy Murray

How does men’s football in the UK learn from 30 years of silence?

Federer out, Alcaraz in – can tennis’ new star fill the shoes left by the departing king?