In the feature article from our latest Zine, ICONS, sports columnist Alex Reid examines our intrinsic need to idolise those who achieve greatness despite their epic failings, not because they do not appear to have any.

Diego Maradona and our deal with sport’s devils By Alex Reid

Diego Maradona and his bitter rival from a previous generation, Pele, went head-to-head in football’s Player of the Century vote in December 2000. Pele – record goal scorer for the most football-crazy country on earth, the only footballer to have won three World Cups and the all-smiling, widely-venerated, heavily-endorsed face of the game in the 1960s and 70s – was expected to win the award.

He did not. Pele polled a paltry 18.5% of the vote. Maradona – whose rap sheet included failed drug tests, shooting journalists with an air rifle, ties to organized crime, legal wrangles over a €37 million tax debt and a messy personal life – earned 53.6% of the worldwide vote. His sum total greater than that of every single other footballer from an entire century combined, from Pele to Franz Beckenbauer, Johan Cruyff to Michel Platini.

FIFA, clearly upset that the award pre-ordained for Pele had gone awry, hastily decided to hold a second vote and among their appointed “Football Family”; a handpicked committee of journalists, coaches and “officials”. Unsurprisingly, Pele came out on top of this particular poll and the Brazilian and Maradona were named joint winners of FIFA’s Player of the Century.

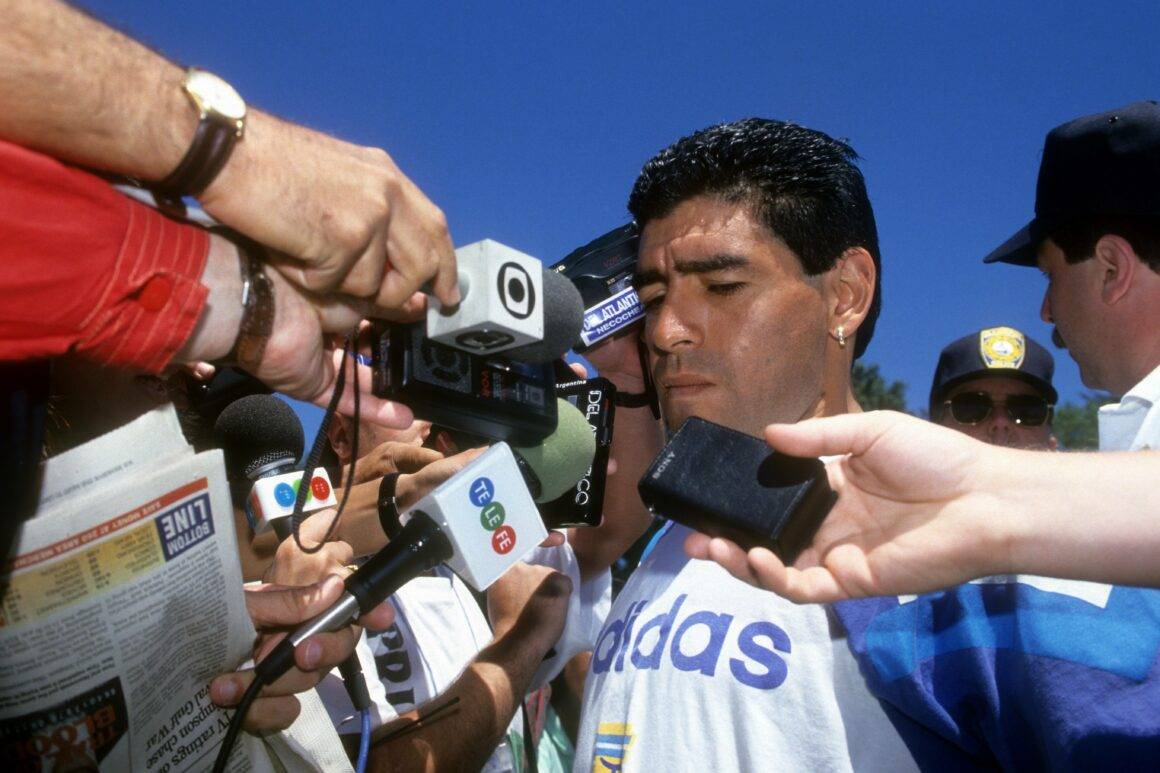

“In 2000, I won the Player of the Century award thanks to the people. Pele was second,” Maradona told reporters, as magnanimous as ever in victory. He added simply: “The award that FIFA gave Pele isn’t worth shit.”

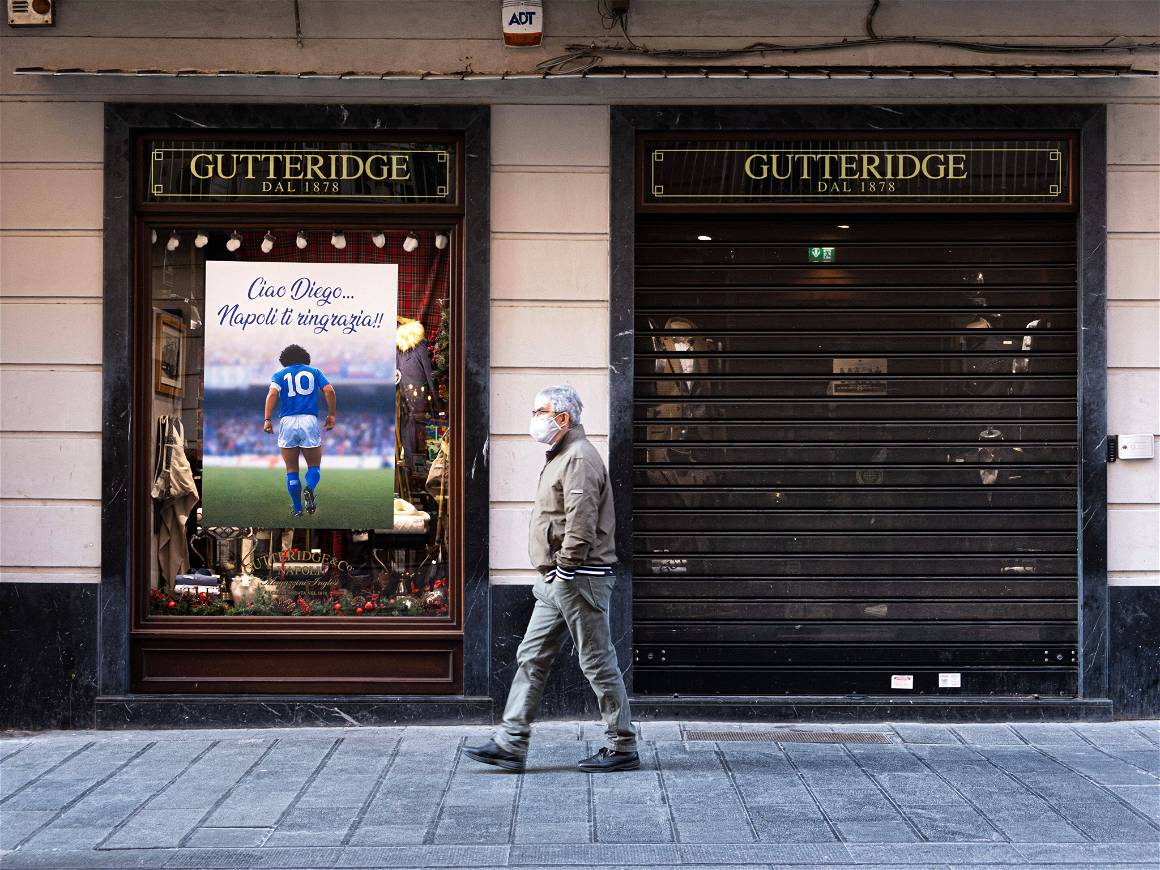

Well, he was always sensational at finishing off a line. Maradona, born to the streets of Buenos Aires, who went on to become the greatest footballer of his generation, died aged 60 in November 2020 after a life of excess.

That he was a hero to the nation of Argentina, where he was nicknamed El Pibe de Oro (The Golden Boy) is hardly a shock. The 5ft 5in Madonna represented not just otherworldly genius on the football pitch, he was feted as an anti-authority rebel at war with the establishment, even if that meant bending the rules to win.

Maradona’s first goal, against England in the 1986 World Cup quarter-final – scored with his hand (though El Diego would later attribute it to “the hand of God”) – was as celebrated in his home country as his second, where he showed his God-given gifts to slalom past England’s defence to score the tournament’s most famous goal. The first goal showed his street cunning, the second his divine ability, in a game that came only four years after the Falklands War conflict between the two countries.

No shock that Maradona was worshipped by the people of Napoli, either. His face was always an ill-fit for an established super-club such as Barcelona and he was far more successful during his seven-year spell with the southern Italian upstarts, pulling down the shorts of Italian royalty Juventus (even if his time at the club inevitably ended in ignominy in 1991 with a 15-month ban after he tested positive for cocaine).

But the undying love of one South American country and one Italian city does not explain Maradona’s global appeal. Nor does his magnificent talent with the ball at his feet justify his ongoing popularity, as the fascination with Maradona went on long after his playing career ended, even as his tempestuous life jolted along, collecting negative headlines at the same rate with which he once racked up goals.

Simply, Maradona was someone you could not take your eyes off, whether on or off the football pitch. FIFA, despite carving his Player of the Century award in half, actually paid Maradona £10,000 (€11,308) per match just to watch games from the stands during the 2018 World Cup in Russia – at least until his antics became too much – fully aware that his mere presence would bring Argentina matches greater media attention. Lionel Messi on the pitch was apparently not enough; Maradona gurning and exhorting in the stadium was required.

That’s because Maradona belongs to a category of sporting figures that runs from Mike Tyson to John McEnroe, Dennis Rodman to Eric Cantona, Conor McGregor to Shane Warne: bad guys. Don’t we just love them?

Naturally, extraordinary talent is a prerequisite with this level of hero worship. But ability does not guarantee popularity, while achievement is not linked to our level of adoration.

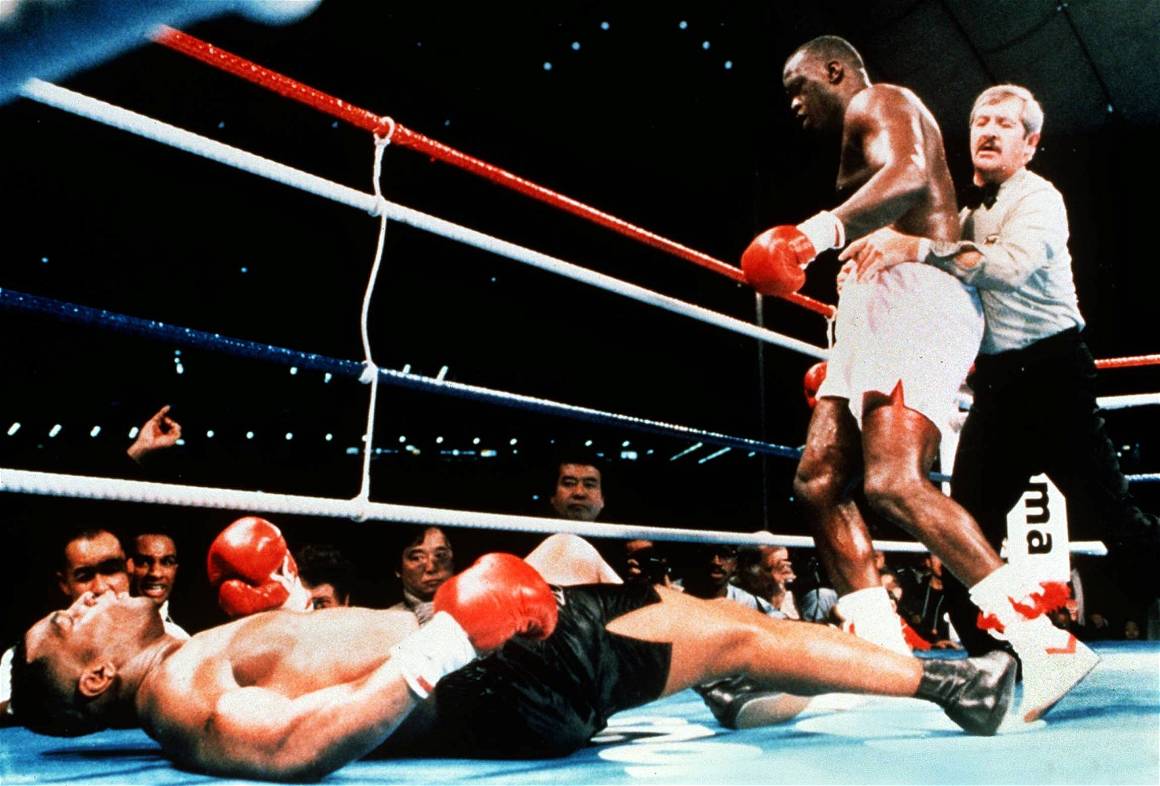

Tyson is the other iconic 1980s athlete Maradona has the most in common with, given their profile, poverty-stricken upbringings, battles with drink and drugs, as well as tabloid-fodder highs and lows. The two met when Maradona interviewed Tyson on his Argentine TV show in 2005 and, inevitably, hit it off instantly.

“Today I was in the neighbourhood where you were born [La Boca] and I think we come from similar places, we have a lot in common,” Tyson told Maradona. “The important thing is that people like us, who come from the same place we do, have always fought to get where we are. And we have had to put up with humiliating experiences. But they could never bring us down.”

His return to the prize ring in August 1995, against the hapless and unknown Peter McNeeley, grossed $96 million worldwide. It shattered pay-per-view revenue records in the US, an 89-second farce of a fight which earned Tyson $25 million. The public appetite for boxing’s ultimate villain had not abated, it had grown in his absence.

In November of 2020, 15 years after Tyson’s career had ended in ignominy with two stoppage defeats, a rusty ‘Iron Mike’ returned to the ring at age 54 to creak through an eight-round exhibition with fellow veteran Roy Jones Jr. The event raked in over $80 million in US pay-per-view revenue alone, becoming the biggest boxing event of 2020.

Like Maradona at the 2018 World Cup, it seems people were willing to pay to watch Tyson just be Tyson, even if he was a shell of the competitor he once was. Undoubtedly we have an obsession with athletes of extremes, gifted at their sport until the turbulence and controversy of their lives overwhelms them.

It is far more complex than just an attraction to sporting greatness. Roger Federer might be the finest, most elegant male tennis player of all time. A fluid joy to watch who can pack courts from Melbourne to Flushing Meadows, even at age 39. But is anybody going to pay tens of thousands of Euros for Federer to sit courtside at Wimbledon in 30 years time, just for the spectacle of having a shy, genteel Swiss man (who just happens to have once been incredible at tennis) watch live at Centre Court? You suspect not.

There is a magnetism, an irresistible allure to sport’s great bad boys that the public find irresistible. At worst, it’s a form of rubbernecking, a morbid curiosity into the private lives of public figures who appear so talented but so flawed. But it is not that simple. That would imply that these are figures of scorn and derision and, more often than not these athletes – from Maradona to Tyson to McGregor – are feted and adored. In some cases, the more that goes wrong for them, the more devoted their followers become.

There is a mystique to these sporting idols intensified by the fact that, to different degrees, they never quite fulfilled their vast potential. That allows us to dream and to speculate, letting loose our imagination. Where is the joy in conjecturing about how just how good Cristiano Ronaldo or Messi or Pele could have been, when they have so clearly dedicated themselves to their sport as to wring out every last drop of their ability?

Far easier to do that with Maradona or Ronaldinho or Cantona. They achieved greatness, people say, but if they hadn’t had their demons – from cocaine to partying to an uncontrollable temper – how much more could they have achieved? The space they left in what they could have achieved, had they committed purely to their sport, becomes not a negative but something to conjure with – room for us to impose flights of fantasy and talk in hushed tones about how much higher each might have soared.

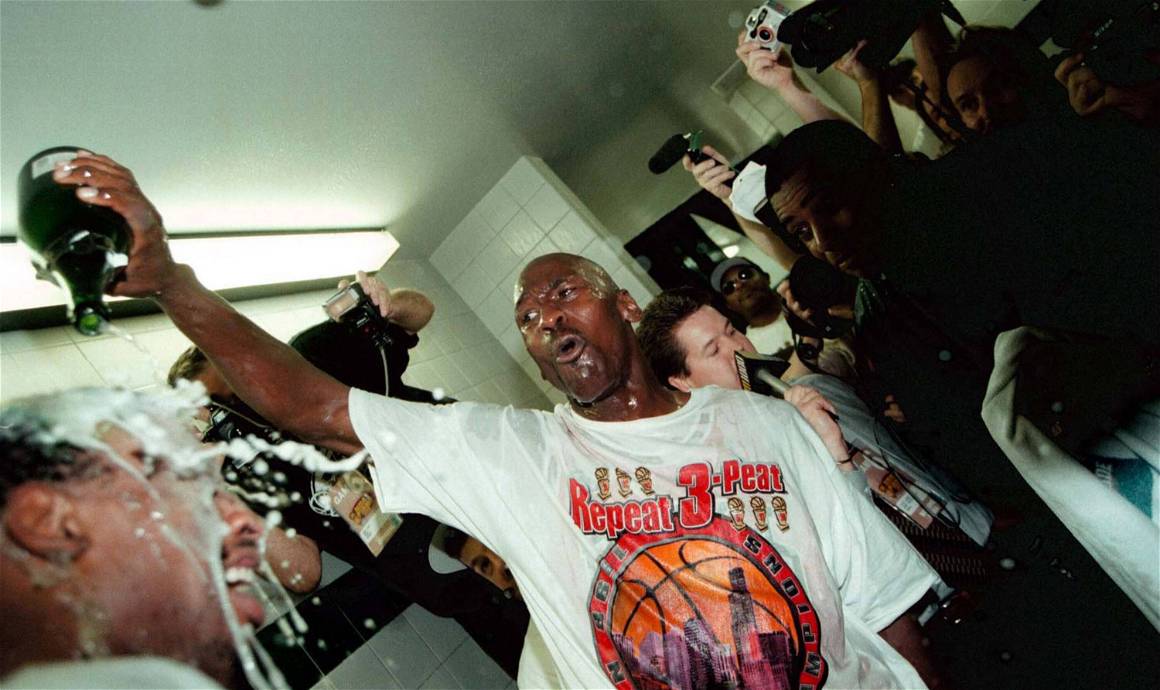

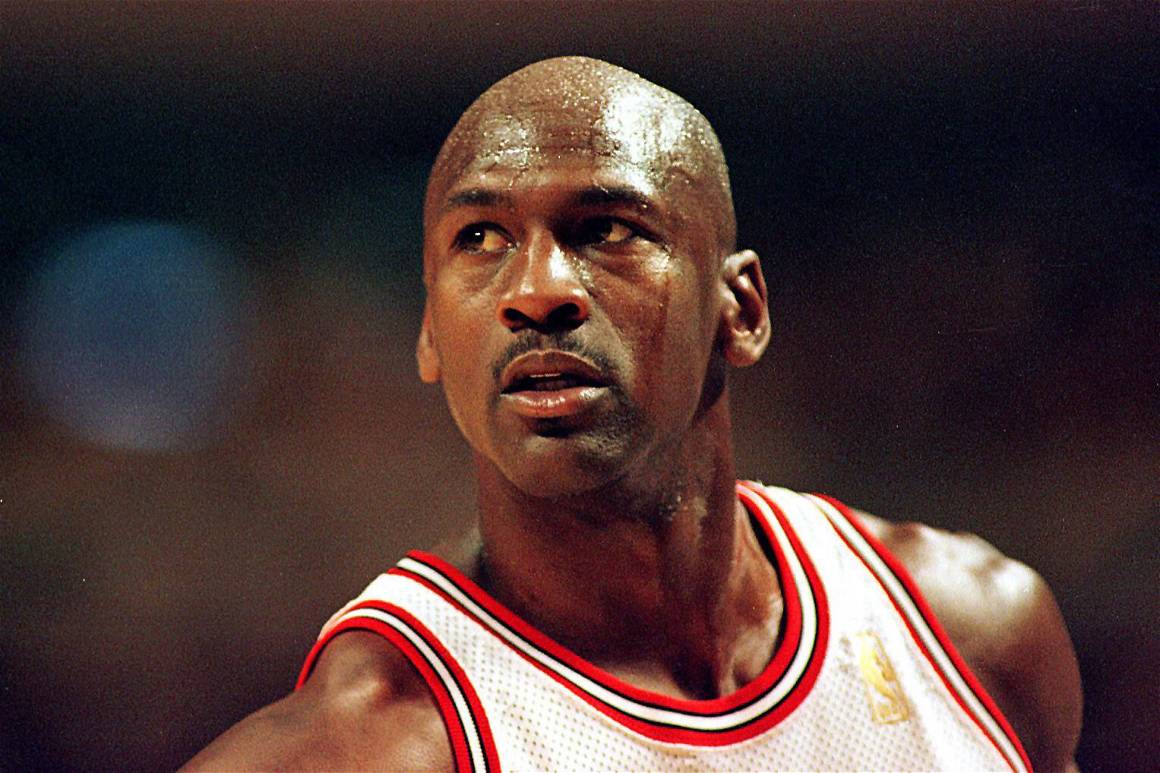

But even that is not a full enough explanation of our attraction to sporting devils. Michael Jordan managed to keep a reasonably clean public image away during his NBA playing days (the hushed-up size of his gambling aside) and undoubtedly fulfilled his greatness on the basketball court. Outside of his brief retirement and mid-career flirtation with baseball, His Airness succeeded in every possible metric in his sport, from multiple NBA championships to scoring titles to points-per-game records that still stand today.

But his Netflix ‘The Last Dance’ series shone a renewed light on the scale of Jordan’s greatness – and ego. As he was himself a producer of the series, Jordan had the power to shape the documentary to his own will, which was a complaint of many in the media. But Jordan still somehow came out of the series as both its hero and its primary villain.

Even the timing of the release was clearly a cynical power-play. Jordan’s position as the greatest of all time had been pretty much without question since his final NBA retirement in 2003. However the performances of LeBron James, as he racked up individual awards of his own and led a third different club to championship status, was causing many to ask the question: was James in fact proving himself superior to even Jordan? Cue ‘The Last Dance’, Jordan’s timely reminder.

A worldwide smash hit, it not only reaffirmed MJ’s greatness but gave those outside basketball a glimpse into the maniacally hyper-competitive MJ. Now a whiskey-drinking, cigar-smoking super-villain, but during his playing career a man who used every single imagined or invented slight as fuel to drive his performances. And also an individual who would browbeat his own teammates if they didn’t live up to his exacting standards.

The flamboyant Rodman, the supposed bad boy of the Chicago Bulls side, actually seemed sweet and somewhat lost compared to the calculated genius at the heart of the team. But while Jordan might not have realised quite how much of himself he was giving away, it made for addictive television. The series was a gigantic hit, Jordan’s greatness was re-established and a new worldwide audience – many with barely a passing interest in basketball – had a fresh interest in the sport’s most overbearing alpha male.

Tiger Woods, another athlete who tried – and dismally failed – to maintain a squeaky-clean public image to keep his sponsors happy, is another who later discovered that it was never really necessary. Despite the myriad of private life disasters and PR trainwrecks, as well as the decline in his own form, that have dogged the last 12 years of his career, the sight of Woods driving off on the first tee of a tournament will still garner greater interest than any other golfer on the planet (including if he returns from his latest self-inflicted setback).

Even those thought completely beyond redemption somehow maintain their status. Lance Armstrong, the biggest global star cycling has ever produced – at one time the claimant of seven Tour de France wins – had the biggest fall from grace of all. Because it was eventually proved that this athlete, who’d survived cancer and become a living legend and inspiration, reached his greatness on the back of organised performance-enhancing doping on an epic scale.

This was a step even beyond the likes of Maradona, for whom drug addiction was a sapping derailment rather than a calculated attempt to get an edge on his rivals. Armstrong’s dismal attempts to justify his cheating also appeared to reveal what many had suggested for years: that he was a bully and a manipulator who aggressively protected his image and supposed innocence, despite the sheer scale of his skullduggery.

Naturally, the Texan was persona non grata in his sport, stripped of his Tour de France wins and given a lifetime ban from competitive cycling. And yet, Armstrong has not disappeared in ignominy, the door has refused to slam shut behind him on the way out. Some supporters (yes, he still has them) whisper that he was just the best at cheating in a cycling era where everybody was at it – why should he be solely punished for that? ‘The Move’, his cycling podcast, has become a huge hit and Armstrong has appeared on NBC’s Tour de France coverage. Clearly, there is still an appetite for Armstrong – or at least to hear from him – despite the irreparable harm he has done to his sport and his own self-image.

So our obsession with sporting villains knows no bounds. If it can’t be deterred by PEDS, jail sentences or violence and abuse, there’s no wonder some have cunningly sought to profit from it.

Floyd Mayweather Jr, an athlete who earned over $1 billion – and counting – throughout his boxing career, deliberately evolved his image into that of the bad guy rather than the hero. For the first part of his career, Mayweather had the nickname ‘Pretty Boy’ and was the owner of a flashy smile and skills that saw him labelled the new Sugar Ray Leonard. But while he racked up the wins and world titles, his box-office appeal was sorely lacking.

So the boxer took it upon himself to buy out his own contract for $750,000 from promoters Top Rank in 2006, and created a new persona: ‘Money’ Mayweather. The arrogant, high-spending, brash, vulgar megastar of his sport. Victory over Oscar De La Hoya in 2007 cemented his new character – which, admittedly, did not seem a stretch for him to play – as the biggest pay-per-view attraction of his era.

Many boxing fans embraced the new “heel” Mayweather, to use the apt wrestling terminology, as the ultimate antihero. Others just sought out his fights in the desperate hope that the cocky, sneering, trash-talking man-child would get knocked out. But everybody watched, everybody paid, and even as his fights became less and less entertaining, ‘Money’s fame and bank balance continued to grow.

‘Bad boys’ is the common shorthand in sport, but it is also clearly not gender specific. Nobody has grasped this concept better than Ronda Rousey, who changed the face of the UFC by becoming the first crossover female mixed martial arts star. To do this, she deliberately took on the role of antagonist, creating a persona that would cause her to be hated or loved, but ensuring that everybody was interested.

“I figured out that I have to somehow make a fight between me and someone become personal to people sitting on the couch,” she explained to this writer in 2018.

“It’s not about making everybody like you. It’s not about being Miss America. Everybody was trying to be Batman [the hero], but there were no Jokers. And The Joker is the most interesting character in the story! If you think about it: the protagonist does nothing until the antagonist shows up and forces there to be a story.”

Maybe Rousey nails the point as precisely as a right hand to the jaw. Sport’s natural heroes engender our respect, our awe, our esteem. But they can be hard to truly love. Something about their own relatively spotless perfection seems too extraordinary, somehow unrelatable, cold and mechanical.

As an audience, we all have flaws. We have failings. We have vices and setbacks, demons and weaknesses. So do the people we love in our own lives, too.

So it is no surprise that we seek out figures like that in sport, to idolise those who achieve greatness despite their epic failings, not because they do not appear to have any. It is relatable and it is human. It is why Maradona received more love from football fans in his lifetime than even the beaming face of Pele. It is why, even now, we cannot resist rooting for the bad guys.

Alex Reid is a sports writer and columnist for The Game. This article is featured and written for the IMAGO Zine #2 | ICONS. Get your copy and subscribe to future issues.