In a conversation with The Game Magazine's guest writer Quincy Mackay, Sarker Protick—winner of the 2024 After Nature Prize for photography, awarded by the Crespo Foundation and exhibited at C/O Berlin—discusses his creative process, journey, and exploration of nature, history, and colonialism’s lasting effects in Bangladesh.

Sarker Protick on Nature, Colonialism, and Change

By Quincy Mackay

Sarker Protick is a photographer born and based in Dhaka, Bangladesh. His ethereal, meditative photographs pause, stretch and warp time. They seem to have a mission bigger than themselves of documenting his country’s past, its nature and its transformation, uncovering and revealing forgotten stories and places.

He is one of two inaugural recipients of the Ulrike Crespo Foundation’s After Nature prize, along with Laura Huertas Millán. Drawing on Crespo’s long career in environmentalism, the prize is dedicated to photographers who deal with the collision between humans and nature and includes an exhibition at C/O Berlin. Protick’s show is titled AWNGAR, a Bengali name for coal located deep in the earth in a red-hot state of spontaneous combustion. It explores the interlinking of colonialism, railways, mining and nature.

Compelled by the archival nature of his work, I sat down with him for a sprawling chat about his photographic process.

“I’m not documenting something that is happening in front of your eyes, but rather I’m archiving things that are not necessarily documented, overlooked parts of history.” – Sarker Protick.

What is your earliest memory of nature?

I don’t think I’ve ever been asked that question. The first image that comes to mind is when we had to visit our grandparents in my early childhood. I was born and raised in the capital city of Bangladesh, Dhaka, but my grandparents are from the north of Bangladesh. To visit them, we had to take a bus journey, but the bus would cross a river, so there was a big ferry, and it would take two hours to cross. It’s a vast river. And as a child – and still, actually – the most exciting part is getting off the bus and finding a place to see the river. I think that journey was my relationship with nature. The landscapes, the delta and the long stretch of river are the main thrust of everything that I understand with nature.

I wanted to ask you that question because we’re both from the city. We have an urban lifestyle, but I think nature still plays an imaginary role in understanding our place in the world. I find your work is a great way to access nature, even from an urban context.

I remember when I was in school studying photography, for my graduation I had to pitch a project. And I immediately chose the river. Probably because of the childhood memory I just described. Living in Dhaka, there’s no access to nature, besides a couple of parks, which are very rare. And I think there was this desire to explore something that is not accessible and makes you feel closer to the real part of the country, because Bangladesh is a river country. When I took up photography, I felt like I could create something that is not like a report but a long-form documentary of the river.

It’s interesting the way you talk about the river. I grew up in Australia, where there’s a strong identity as an island nation. Now living in Berlin, one of the things I miss most is access to the ocean. Because it’s the only place where you can look into infinity, stretching out on the horizon.

That’s vital for my work, I think you can see it in the series “Of river and lost lands”. When you ask why I was drawn to the river, there are two things I remember thinking. One was that it felt like I was at the edge of the earth. If Earth had a border, an end, that was it. Even though it was a river, you don’t see much in the distance, especially during the monsoon season or the winter season. So, it becomes this blank horizon in front of you. So I was curious to explore that vision. And the other one was the smell. It’s difficult for me to explain it here, but if you travel around our country very early in the morning and stand by the edge of the river, there’s this sort of fresh air, the smell of the water or the nature around it. That was something that was very affecting to me, to be close to that.

“In Bengal, through my work on the river, I have been observing massive changes over the years. In our Bengali calendar, we used to have six distinct seasons… Over the last 15 or 20 years, I’ve seen it all change… Now, jokingly, we say it’s just summer, summer with some rain, and a little less summer.” – Sarker Protick.

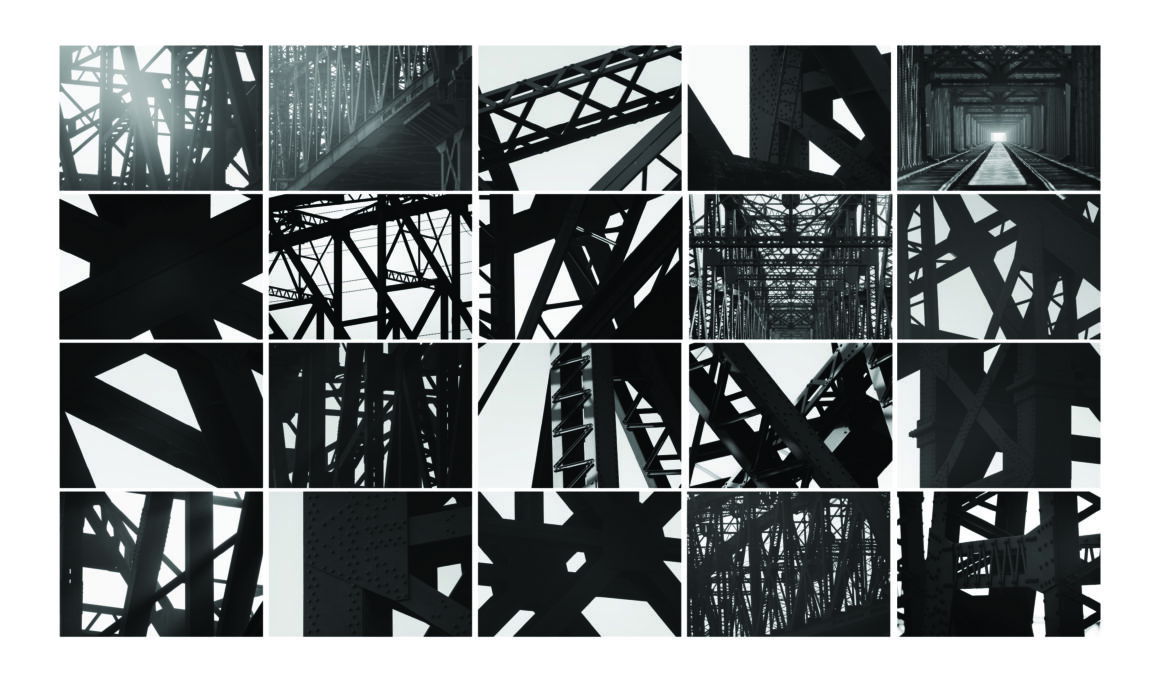

If we can turn to your exhibition here at C/O Berlin, “AWNGAR,” which presents a clash between nature and industry. I see a contrast between the presence and absence of nature or industry. For example, in the work “Foliage,” where we see the nature around the Chinakuri mine, but the mine itself is absent. Or “Hardinge bridge,” where we see the bridge, but not the river it’s crossing. How do you play with that relationship?

So that bridge is basically in the same place as the works from “Of river and lost lands.” I have been observing that bridge for some time. The polaroids in the exhibition are of a town also by that river. This is not anything planned, right? This is all coincidence. My interest was the river, but because I didn’t live there, I went there on several trips in a year, and once you start to go somewhere, you start to see other things in that area. Where is the bazaar? Where is the restaurant? Where is the hotel? Where is the school? So I used to always pass by this particular segment which was very different in terms of the architecture and the trees. The trees were rain trees that were planted by the British Raj, which you don’t see anywhere else. It’s like a pocket where you enter, and suddenly you’re in a different kind of place, a different time. Then I realised this district also has the largest railway junction in Bangladesh. All the lines connected there, and they decided to build this bridge, basically to connect the western part of Bengal with the east. It was completed in 1915.

I have photos of the bridge in a setting where I photographed the river, where it is like a part of the river ecosystem. But when I started to explore the railway history, then that bridge became more of a character. A lot of people are very proud of it, for some reason. I think one of the reasons is because it’s very old, so people say: “Oh look at the British, they built such a good bridge.” So that sort of strange mentality is there. But I was also interested in the material of steel, because that’s connected with coal. It’s also just a huge element of the railway network in our country.

I started the river work in 2011, and in 2017, so after 6 years, I started to become more interested in railways. I initially made a short video about the first railway station that was established by the British in our country. It’s a small station, and it’s just across that river, on the other side of the bridge. The film looks into the history of the partition of Bengal, but also uses the first rail system as a protagonist. Around 2020, I also wanted to make a series of polaroids about that railway town. At that point, I was also travelling for a different project which is related to partition and architecture, called “Spaces of Separation.”

After India and Pakistan were separated, there was a huge migration that happened, and a lot of landlords, who were Hindus, went to India, and all their properties were abandoned. So I was visiting these old towns, and often in these old towns, you’d end up seeing these railway stations which had a very similar architecture. That made me think, “Okay, so it’s a huge network actually, it’s a British infrastructure that exists throughout our country.” In many places, like Calcutta, Mumbai, or even Australia, you can still see a lot of British monuments and buildings.

Absolutely.

There’s not as much in Bangladesh. But the railway network is still there.

So it’s like the last trace.

Right. So then the work moved on from just the polaroids of that small town, but became about travelling to a lot of other districts across Bangladesh, to find these main British stations, and the old junctions, the railyards, the workshops. And I found all of these great buildings. There’s a big theatre, an office, a workshop, and so on. And then this house: this is the office for the construction of the Hardinge bridge. Do you know the term Bungalow?

No.

It’s a housing style.

Oh, right, a bungalow. Yeah, of course!

So that word comes from Bengal actually, because the design was developed there. So this is a very typical Bungalow of British railway officers.

When they build these towns, they build everything: Schools, hospitals, colleges, theatres, auditoriums, and so on. So the idea of this town was a very British concept. I started to explore these railway towns, which became the work “Crossing.”

So it’s almost mapping settler colonialism as it’s going through the territory that maybe isn’t as present in other parts of Bangladesh.

Yeah, exactly.

What about people? There are almost no humans visible in any of the photographs in the exhibition.

I don’t like to photograph people unless they have a particular reason to be in the work. In AWNGAR, there are two photographs of the human figure. Both are female. In the last room, you see this girl from behind. She is a villager working in the mine, standing across these big tracks. You see the machines, the altered landscape, the electric poles and wirings of the railway. But it’s a very green, rural place, so there’s a lot of wilderness. Nature is contrasted with sharp lines, and wires – with the human intervention in nature.

So the girl is almost like a witness. Not necessarily having any say in any of it. A lot of this is not based on what we wanted, or asked for, but it is there. It is human civilisation and how it has transformed nature. And she is the witness.

That’s interesting to me as a historian, because it feels like you’re unlocking marginalised voices and perspectives that are often absent from the archives with your photographs, which have this documentary or photojournalistic quality.

It’s much more archival. I think my style, in everything – not just the visual approach, but also the method of working – has nothing to do with photojournalism, for sure. I’m not documenting something that is happening in front of your eyes, but rather I’m archiving things that are not necessarily documented, overlooked parts of history.

Right. Studying colonial history, you find plenty of stuff about what the British did, or the French did, but you can’t find many of the voices of the people who were actually being colonised. So I’m intrigued by the idea of using photography to capture those hard-to-reach perspectives.

It’s even just about finding local views, which are only discussed on a very small scale, perhaps, within very few intellectual communities. But it is not explored on a larger basis, and especially not visually. For example, in “Spaces of Separation”, you see the housing, but nature is also a very strong presence there. These houses were owned by very powerful landlords who had to flee when the country was divided. That’s how the British always worked: they divided and ruled, so they created a separation between the Muslims and the Hindus, and that created separate countries. And this is not necessarily visually archived in our country. Even in the archaeological department, they have very basic leads, but there is no visual reference.

So initially, I was trying to make a list, to go to all of these places, but I’m not an archaeologist, right? If I’m working in history, it’s a lot to do with reading, and learning in the classroom. But I am an artist, and if you’re working with the medium of photography, you actually have to be in the real world and travel to these places – sometimes very remote, sometimes never actually mentioned anywhere. Sometimes you didn’t even plan to find it. I remember once going to a place based on a paper from the archaeological department, and going there and finding nothing. It’s just the sign that’s still there, that says “This site is under the supervision of the Archaeological Department of the Government of Bangladesh. No writing on the walls, no taking anything,” you know, all these regulations, on a big blue sign board.

And then you enter, and you see there’s nothing. There’s literally nothing there. Just the land, that’s it.

But then you ask the people there, what happened? And the people say, “Oh you know, people took all those things, so long ago, over the years they have taken everything, nothing is there. But why don’t you go twenty kilometres further north? There is a nice building there.” And then I go there, and I find a very interesting place, which is never mentioned anywhere. You have to be cautious of that – that you might not find what you intend to find, but you have to always stay open that you might find something different.

“What do you expect if you do that to something? —keep brutally extracting it over the years— Like just think, if I hit you now, how would you react? And if I keep hitting you, over years and years, and exploiting you, how will that turn out?” – Sarker Protick.

That sounds very familiar; that sounds a lot like archival work, where you end up going down an unexpected path.

So this series started from the river, and different branches started to give. The railway, and that then took me to the history of coal mining. And it’s not just the economic history that links those two. In our region coal mining was initiated because of opium.

There was a huge opium war, and it was connected with the British trying to sell a lot of opium to China. One important individual was Dwarkanath Tagore, a Bengali industrialist, and he was in charge of the opium trade. In order to be able to supply more opium, he needed coal, to have faster shipments. He wanted to do better business for the British Empire, and so established coal mining and railway industries in order to supply more opium. And what is opium? Besides all its uses, at the end of the day it is a plant. It’s very natural. So maybe, I don’t know, someday if I get the time, I would like to explore that. But I have to do a lot of reading for that.

We’ve spoken about the past, let’s turn to the future. The After Nature prize is dedicated to artists who deal with climate change, which feels like the elephant in the room in your work. What do you think about the future?

In Bengal, through my work on the river, I have been observing massive changes over the years. In our Bengali calendar, we used to have six distinct seasons, and each season had two months. For example, a monsoon consists of two months. One is Asharh, and the other one is Shrabon. And the rain in the first is different from the rain in Shrabon – or it used to be. Over the last 15 years, 20 years, I have seen it all change. It has become just three seasons. Jokingly we say one is summer, one is summer with some rain, and one is a little less summer. And then, of course, all the natural disasters, the floods, the cyclones, are always there.

If you want to find out why and how it all started, you have to talk about the nature of extraction. That’s in the last room of the exhibition, where you see the earth and how brutally we extract it. What do you expect, if you do that to something? Like just think, if I hit you now, how would you react? And if I keep hitting you, over years and years, and exploiting you, how will that turn out?

Do you feel there’s an activist quality to your work?

It’s more about a deeper sense of being aware, I suppose. I don’t see myself as an activist. Maybe an archivist perhaps. An archivist of the present, and also whatever I can from the past. And if those materials can help us to be a little bit aware of what has happened, that’s all I can do. In the end, I’m just someone who’s deeply passionate about the medium, so it’s almost a selfish need to learn things, to visit all of these places. It is a personal need to feel more connected to the immediate world that surrounds me. And I’m going to do it, even if that makes the mentality of people change or not. You need to keep doing it, and many people need to keep doing it, then that will be the change. My role is a very small spoke in that.

The credit of the cover photo | Sarker Protick, “Hardinge Bridge, Padma River,” from “AWNGAR,” 2024, courtesy of the artist.

About the Author

Quincy Mackay is a German-Australian culture journalist based in Berlin, covering arts and photography. He studied history, researching care work in the Algerian War of Independence and exploring the legacies of colonialism. He also works as a pedagogical tour guide, covering the history of the city of Berlin with a focus on the Berlin Wall.

Read more interviews in The Game Magazine:

Two Years After Iran’s Uprising: Yalda Moaiery on the Struggles of Photojournalists Who Captured the Protests

Tom Griggs on Creativity, Photobooks, and the Photo Scenes in Colombia and Mexico