In an interview with Jens Pepper from The Game Magazine, photographer Tom Griggs reflects on his creative journey, his blend of personal and found imagery, and the evolving photography scenes in Colombia and Mexico.

Tom Griggs on Creativity, Photobooks, and the Photo Scenes in Colombia and Mexico

“It can be easy to forget that patience makes projects that last.” – Tom Griggs.

Tom Griggs was born in Manchester, New Hampshire, USA, in 1974 and grew up in Minneapolis, Minnesota. He holds a bachelor’s degree in American studies from Wesleyan University, Middletown, CT (1997), a fine art bachelor’s degree in painting (2002), and a fine art master’s degree in photography (2009), both from Massachusetts College of Art and Design, Boston, MA. Currently, he lives in Medellín, Colombia and Mexico City.

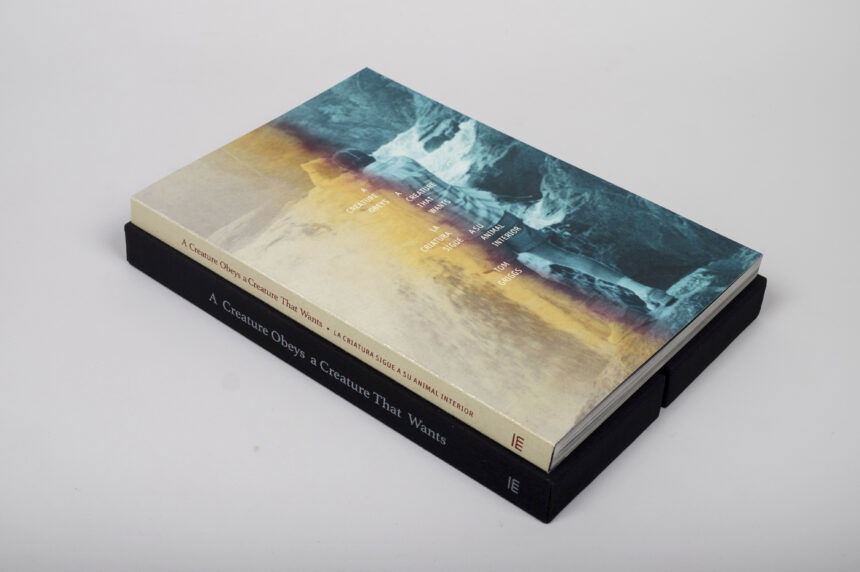

He is a photographer, editor, educator and writer. His photobook, “A Creature Obeys a Creature That Wants”, which had just been published by mesaestándar in Colombia, is a poetic hommage to his father. In this conversation, he talks about his life and work as a photographer and about the photo scene in Colombia.

What did you start with as a professional photographer? Did you look for commercial assignments, or were you interested in art or freelance documentary projects? Or maybe both at the same time?

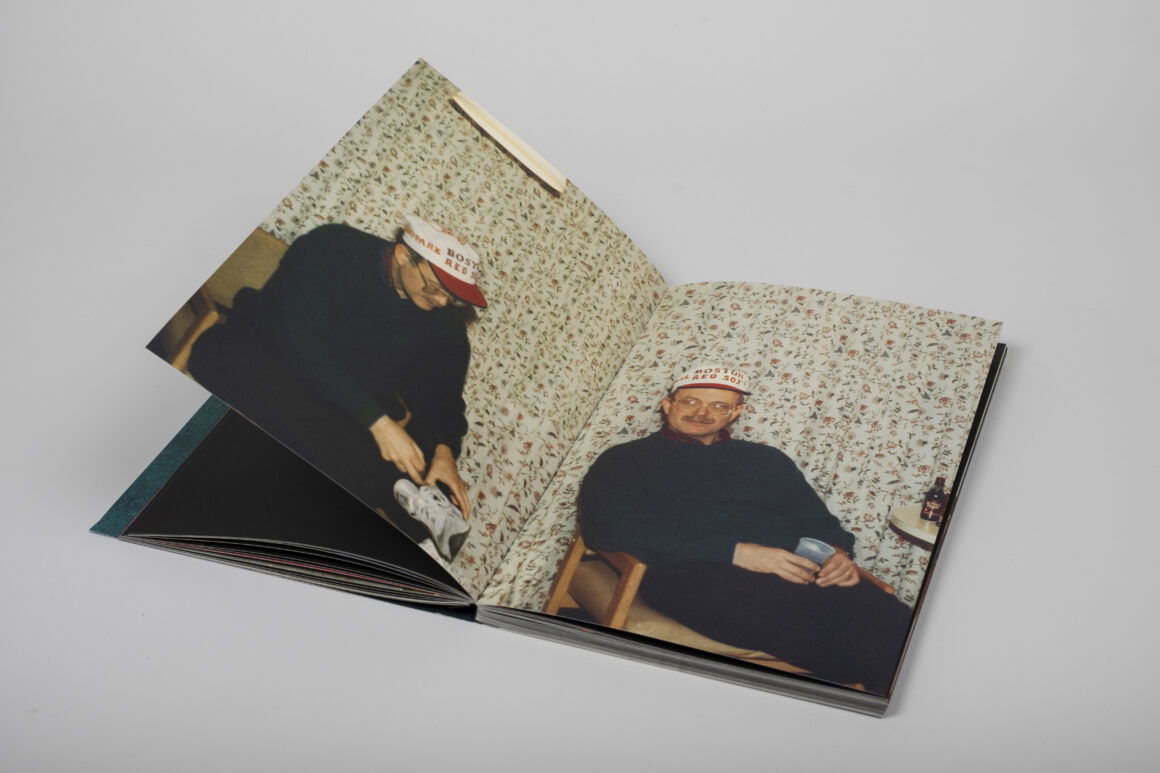

I started working as an assistant for commercial photographers in Philadelphia as well as with my own initial personal photography projects. Even in the first days of my personal photography practice, I explored the medium widely as I still do today. While I have always had an interest in observational photography—photographing in the streets or within a specific place or community—I have also enjoyed exploring photography in ways that move beyond those traditions. For example, when I was in my first classes at the university, I made a number of prints quite distant from the original negative by cropping, cutting or purposefully over or underexposing the negative after being inspired by a show of the work of F. Holland Day at the museum next to the school. Today I mix my own photography with photography from other sources in several projects, and in two of my most recent books, I work with both images and creative nonfiction texts.

What do you mean by creative nonfiction texts? Texts like the ones about your father’s life in “A Creature Obeys…”?

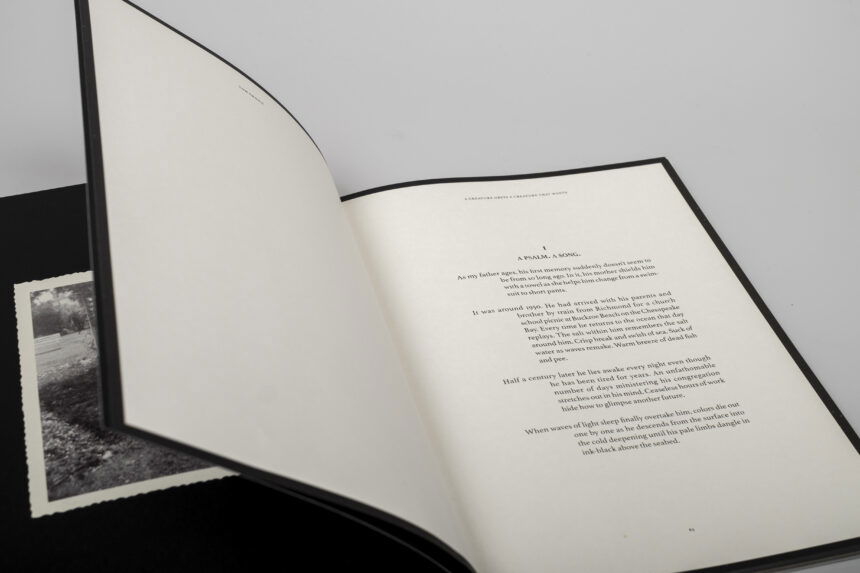

“Creative nonfiction” is a term we use in English to describe a genre of writing in which literary schemes and devices are used to tell factually accurate narratives, exactly like “A Creature Obeys.” The genre contrasts with academic writing or journalism, in which factual narratives do not generally employ a novelistic or literary style. Writers that fall into the creative nonfiction category would include people like Tom Wolfe, Joan Didion, and Norman Mailer.

When you mix your own photos with pictures from other sources, like family photos in the mentioned book about your father, it is the overall atmosphere created that counts, not so much the single photographs. This is a highly subjective representation of one’s own feelings and memories in relation to the chosen topic. Such books are not for the masses. In the case of “A Creature Obeys …” you need readers who will engage in this very personal way of dealing with your own story and that of your family. It is more like reading a poem, not like reading a story. Why did you choose this way of using photography to make a work about your father?

To take a step back and to answer from the widest angle first, when something—a quote, a curiosity, a question, a doubt—sparks within me the idea for a body of work, I begin to track my thoughts around that idea. If I continue to think about the possible project over days and weeks, that means it is important enough to set aside time for it. I begin to make initial images and write if the project seems like it will require text.

When I begin, I don’t have an idea of how the project will ultimately look, and I do not have one single visual approach to working on all of my projects. Instead, I work outwards from the initial project idea to discover an aesthetic that I feel is appropriate for that particular project—one that has the right tone, the right atmosphere, and the right pitch for the subject. My projects usually end up changing their look quite a bit in the early and middle stages of working on them until I find the aesthetic response that feels “right” for the body of work.

In essence, at least in my practice, every project is about encountering the right tool for the job. It takes time, sometimes years, to find the right tool. It is not something I decide on, but rather something I find only when I know my material deeply. Usually, I work for a long period on a project, then have some sort of key image appear, or have an insight that makes everything clear in terms of how the project needs to be presented. I discard much of the material I’ve been working on. It is unequivocally painful, but I can work quickly now that I know what the project wants to be. Everything begins to lock in place. I have the criteria I have been looking for to make final decisions.

In sum, this way of approaching my projects means that each one ends up having a look that is usually quite different from my other projects. Each one responds to its own internal logic to arrive at an aesthetic presentation appropriate for the work.

“A Creature Obeys” followed this path. The initial PDFs of the work have nothing from the finished work. I just looked, and it went through 34 versions to arrive at the final book! It took that long to encounter the poetics that would not merely describe the facts of what my father experienced and present his story in the thinnest and most literal way, but that would also transmit something of the emotive space of his experience. For the right reader, hopefully their heart, emotions and guts are all responding to the material, not just their eyes and minds. This felt like the right way to honor my father’s story.

You mentioned F. Holland Day as a source of inspiration for some early works. Were there others, also more contemporary photographers, who fascinated you and whose work might have had an influence on your own development?

There are probably few historic photographers whose work has aged as poorly as F. Holland Day’s! But I really did fall for his printmaking early on in my exploration of photography, especially their compressed tonal ranges in which a middle gray can feel like a highlight, as well as the soft focus on his subjects.

There are a few contemporary photographers whose work I find influential, or maybe “inspirational” is the right word here. They come from a wide-range of styles of work: Jacob Aue Sobol, Gueorgui Pinkhassov, Taryn Simon, Masao Yamamoto and Dirk Braeckman come to mind. More commonly, I come across an exhibit, page through a photobook or have a conversation with someone who inspires me as opposed to someone’s entire career being an inspiration. Lieko Shiga’s book Rasen Kaigan is something I return to over and over. I was a guest critic at Alec Soth’s workshop in Minneapolis last month and I met Karolina Wojtas, a Polish photographer, and our conversation was another such inspiration. She makes work I would never and could never make and does it very well. That tends to be the type of conversation I find artistically inspiring, as opposed to talking with someone who works more similarly to the way I do.

The largest influences on my photography, however, are not photographic. Writers inspire me the most, then movie directors, then painters; maybe then photographers? The medium in which an artist works is less important to their influence on me than their sensibility and how they interface with the world. By that, I mean I don’t care that Robert Frank photographed a road trip; I care HOW he photographed a road trip. Art is indeed the “how,” not the “what.” The most influential artist for me right now would be the Canadian writer Anne Carson. I’m also reading Cormac McCarthy and Maggie Nelson and watching Aki Kaurismaki movies, as well as the series “The Americans.”

You include text in your photographic work; literature is an inspiration for you. Did you ever think of a life as an author instead of a photographer?

I did. I’m sure that in the multiverse, there is a version of me that is a writer! My first attempts in the creative arts were actually with writing. At Wesleyan, I took a short story writing class that I loved, and then I was invited to be a teaching assistant for the same class the following year. I had some momentum, and I wanted to continue taking classes. The school had a small writing program whose most important faculty member was Annie Dillard. She had a class that was essentially the gateway into the advanced classes in the creative writing area. You had to apply for her class with a story. I worked on one based on events that had happened at my high school when I studied there. I remember my nervousness as I approached the department office to pick up my story with the accompanying note to tell me if I had been admitted to Dillard’s class or not. In her encouraging but crushing rejection, she wrote that she liked my writing; she told me to write about the world beyond myself. She hadn’t responded to my work’s semi-autobiographical component. That closed the path to taking more creative writing classes at the school. I ended up leaving my interest in creative writing behind for more than two decades until I collaborated with Paul Kwiatkowski on the book Ghost Guessed.

Tell me about this project.

Sure. It’s a collaboration published in 2018 with the writer and photographer Paul Kwiatkowski by the Colombian press Mesaestándar. I had talked with Paul about featuring his book And Everyday Was Overcast on a website I ran during the 2010s called Fototazo. He proposed that we do a “creative interview.” I’m still not quite sure what he meant by that! But in practice, we got on Skype calls late at night with beers in hand. I was in Colombia, and he was on a road trip through the Southwestern United States with his girlfriend.

From the start, we didn’t talk so much about his book as much as we took deep dives into media and technology, US popular culture, events we had both lived through, and the strange parallels we started finding between our lives. We audio-recorded the conversations,and then I would go through the recordings and pull together the most interesting parts into a Word document. We quickly realized we weren’t working on an interview about his last book, but rather a book of our own. We polished our cultural critiques and laid out the text in a PDF with his and my photography as well as images pulled from many other sources, including the media and family archives.

Then one night, right around the time that Malaysian Airlines Flight 370 disappeared, I told him the story of my cousin Andrew Lindberg, who had similarly disappeared in a small plane he was piloting over Minnesota,where he and I had grown up. Paul immediately recognized the importance of this story for our book. It gave us a human story around which to hang all of our theory and critique. Our finished book is a meditation on vertical free fall structured narratively around the disappearance of MH370 and Andrew’s story. The book explores how that sensation of free fall can be used to describe periods of our lives in which we don’t know our next step and feel lost within our own narratives.

You live in Medellin, Colombia, now. What brought you there?

Like a lot of foreigners who moved here before Medellin’s tourism boom, it’s a love story. I met a Colombian woman at an arts residency program in New York State, and eventually we married. She received a full-time position teaching at one of the major universities in Medellin in 2010. We moved here initially for two years to see how it went. I’m still here 15 years later even though our relationship ended a few years ago.

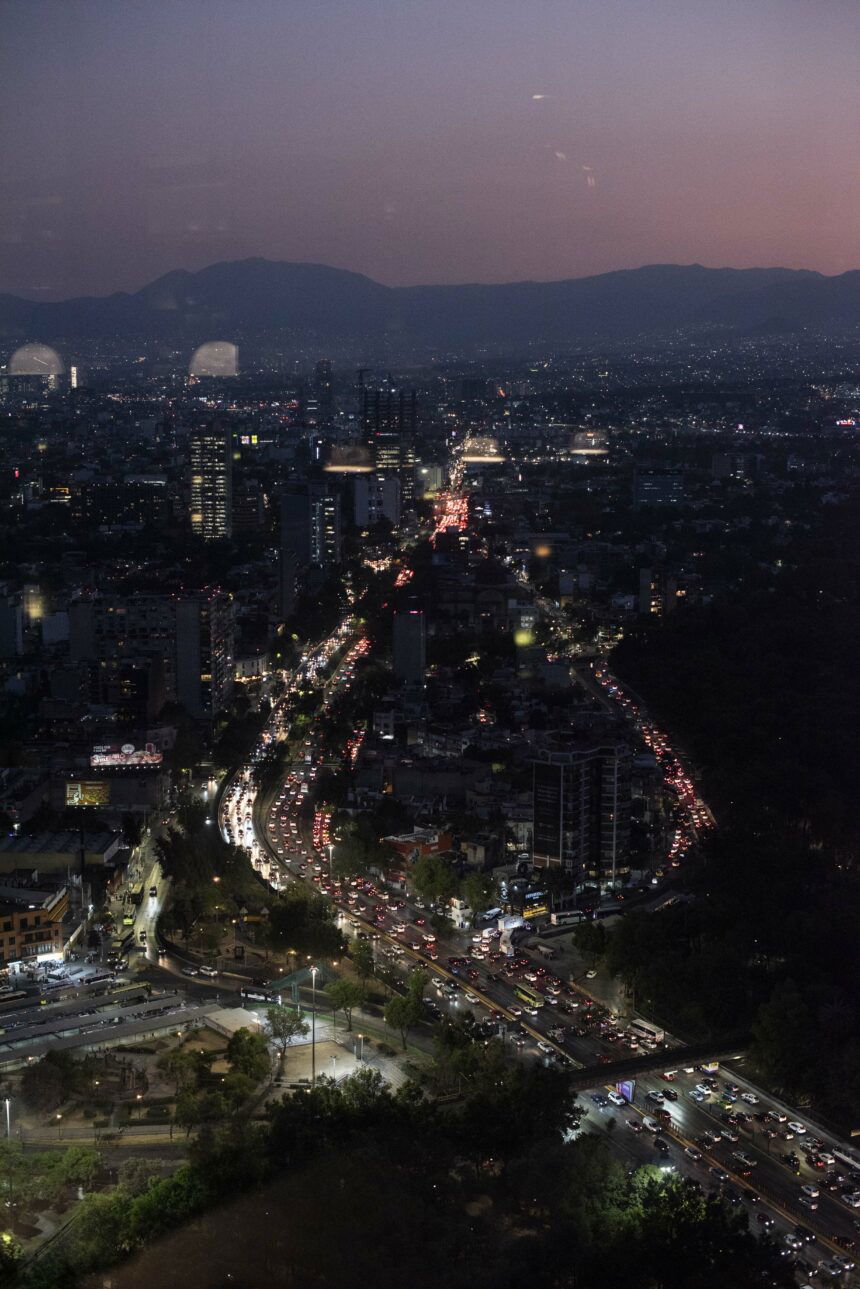

When our relationship ended, I thought about moving. I moved to Mexico City for three months in early 2020 to explore the possibility of it becoming my next home. I have been traveling there for years, and I have important friendships there. The city’s art and culture scenes, its history, and its high desert light have always drawn me toward it. While I was there the pandemic started. Three months became almost three years as initially, travel became impossible, and then because I had connected deeply with people I met and the city itself. Now, I have a foot in both Medellin and Mexico City.

You explain what you like about Mexico City, talking about the city’s art and culture scenes, the light and so on. What do you like about Medellin? How does the culture scene look there? Is there a photo community?

Beyond personal reasons for enjoying living in Medellín, such as my apartment, long friendships, and my dog, the city has a perfect climate year round. The culture values friends, family and time together as much as work, which I don’t always find the case in my native United States. People are warm. There is a fluidity in everyday life and in how people relate to each other in Colombia that I have come to appreciate. It seems that living through decades of violence and with the presence of death has led to a culture of living for today. Friends will stay out with you for an extra drink and another dance if you’re having a fun night, even if it means you’ll be tired at work tomorrow. Medellin is also cheap, cheaper than Mexico, and that affords me time for making books that don’t generate income directly.

As for the cultural scene, Medellín has an energy of creativity. If I had to say what its strengths are in the cultural industries, however, I would say fashion design, architecture, music, dance, graphic design, and probably literature, before I would mention the creative arts beyond Fernando Botero. Bogotá is Colombia’s international-level arts center; Medellín by comparison, is a fairly small scene.

In photography, traditionally photojournalism has been Medellín’s strongest area, and the area that has controlled the community and established the parameters of discourse around the medium. I still think this is still largely true. Commercial photography is strong here as well, and taken seriously as a form of artistic expression. Art photography has always been an area of more limited presence in Medellín, as far as I can tell. There are strong art photographers based in the city, and they generally know each other, but they don’t tend to hang out much or collaborate. More than a scene, it feels to me like a group of individuals doing their own thing.

You are also a teacher. What do you teach, and where?

That’s right. I taught for a long time at the Universidad de Antioquia, as well as at the Fundación Universitaria Bellas Artes, both in Medellín. I appreciate those years a lot and maintain friendships with many former students. It has been a pleasure to see them become important parts of the art community in the city, both on the administrative side and the creative side.

The pandemic opened up the possibility of teaching online with the boom of interest in remote classes. I have been teaching at the International Center of Photography in New York for the last few years, as well as teaching both online and travel classes in Colombia with Maine Media Workshops. The flexibility of teaching online works well for my life right now, with a base in Colombia, but also a presence in Mexico and the United States as well.

How often are you in the States? Are these visits mainly to stay in touch with friends and family, or are they also essential for not losing career opportunities and possible assignments there?

I’m there three or four times a year between trips to Minnesota and the East Coast. The trips cover a bit of everything: seeing my parents, my brother and his family; maintaining long-standing friendships; checking in with friends and contacts in the photography community, including a number of professional friendships that have become deeper personal friendships over time; working on a house that I have in Philadelphia, the rental income from which helps subsidize my work on personal projects; and also occasionally to get to events like the New York Art Book Fair. I don’t do much assignment work at this point in my life, and so I don’t need to be there in terms of those types of opportunities.

Much of the photography created in the different national photo scenes in Europe by the younger and middle generations tends to look quite similar to each other. You can see trends regarding themes, aesthetics, and approaches to deal with certain subjects. Lots of stuff is quite academic. You really have to look for interesting works. In Poland, it is a bit more interesting at the moment; there are more individuals around with fresh ideas. You mentioned Karolina Wojtas yourself, who certainly is one of the most interesting Polish photo artists of her generation.

How do you see the young generation of photographers and photo artists in Colombia and Mexico? Are they following international trends – if yes, which ones? – or don’t they care about what’s popular elsewhere and develop freely?

I know the younger generation in Colombia better than in Mexico, having taught for many years in Medellín and having lived there longer, but I think my answer for both countries would be similar.

Many photojournalists and documentarians seem to place work with international media as a goal. It makes sense. The pay is exponentially better, and it brings prestige, recognition and, in turn, more work. This means that their style generally points toward international tendencies or the very specific vision of one of the photo editors at top foreign newspapers and magazines. For example, photojournalists from Colombia and Venezuela who work with The New York Times work with a photo editor with an aesthetic preference for camera work that prefers underexposure and saturated colors. It’s as if the entire region was a stop or two darker than the rest of the world when you look at the paper.

National Geographic is another media outlet that contracts a lot of photographers I’ve had the chance to get to know in the region. The style is distinct from that of photographers who work with the Times, but again, there appears to me to be a significant degree of work made in the established modes of the magazine because that is what gets published and generates more work.

Within the smaller world of fine art photography, I would say that in my experience, the goals for younger photographers tend to align with the goals of young photographers everywhere: these days, primarily to get a book published, perhaps also to find a gallery or exhibition opportunities, and maybe to have the work featured in certain online spaces. The majority of photographers would ideally work with presses and galleries with international reach, which necessitates creating work within certain parameters. This then creates a degree of overlap of visual expression with work made in other parts of the world as regional photographers compete with photographers from other parts of the world to, for example, publish a book with MACK, which is interested in work that fits within a certain aesthetic range.

Unfortunately, this works against the evolution of idiosyncratic regional expression. It speaks to the importance of continuing to develop local presses and arts institutions with an international presence. There are some encouraging examples, including regional publishers that already have international traction and significant market presence, such as RM based between Mexico and Spain, as well as others that are getting more traction, including Raya Editorial based in Manizales, Colombia and KWY Ediciones in Lima, Peru. Those last two presses provide options inside the region for creating books that align with the interests of editors from the region, opening up the possibility for work to be published here that might not be published in other markets. Additionally, local printing costs are much cheaper than in the US or Europe, allowing more talented photographers access to publishing that are economically shut out of other markets where presses ask for an increasingly large share of the printing cost or have become borderline vanity presses asking for massive “design fees.”

To zoom in, Raya has published some strong books by photographers that I value that I think would have been hard to imagine coming from a European or US-based press. One example that comes to mind is Gabriella Baez’s La gente deprimida tiene sexo sucio y ganas de morir. Santiago Escobar-Jaramaillo is the press editor, and he has a particular interest in publishing Latin American authors, and he has a particular eye for design and material decisions about books that are unique to him and feels like it has something about the region.

In terms of the work of younger generation art photographers, I think that they largely look to international photographers as references and inspiration, as well as a few local photographers that have broken into the international conversation, such as Jorge Panchoaga and Juanita Escobar, both from Colombia. There are occasional visual trends between photographers, such as an extended run on darkness as a defining visual aesthetic for a number of years. The most significant difference between photography in Colombia and Mexico as opposed to the rest of the world, however, would be found in the level of themes chosen by photographers for their projects. Some of these themes are regional; some are more country-specific. For example, in Colombia there have been a lot of photographers working in all styles of photography on the country’s armed conflict. Another related topic that many have worked with is memoria – a cultural push to remember its violent past in order not to forget it and not to repeat it. Several others have worked with drug production and trafficking, still others on life in marginalized areas of the country, especially on the country’s Pacific coast. Mexico would similarly have its own set of repeated themes, as does Brazil, as does Argentina and so on.

Let’s come to the last question. Do you fear that one day you might run out of ideas or repeat yourself?

I don’t fear running out of ideas. I have working documents on more projects than the rest of my years will allow me to do – and the list of possible project ideas gets longer, not shorter! I guess I don’t believe that I fear repeating myself either. I have an “appropriate fear” of repeating others, and I work to make sure that a project of mine finds its own space in an increasingly dense photography landscape where adding to the conversation becomes harder and harder. Another fear I have would be that I put work into a world that doesn’t deserve to be there yet, and that I haven’t gotten everything out of a project development process that I could have. Sometimes, in the social media-impacted world in which we live, it can be easy to forget that patience makes projects that last.

This Interview was conducted via email at the end of July/beginning of August 2024. A few passages were shortened for this publication.

The credit of the cover photo: Tom Griggs, from A Creature Obeys a Creature That Wants.

Read more from Jens Pepper here.