Muhammad Ali is the most famous, most photographed, most revered, most widely analysed and discussed athlete in sporting history. Somehow he is also the most misunderstood. Words by Alex Reid.

Muhammad Ali: the world’s most misunderstood athlete

There is a heavyweight logic behind that apparent contradiction. Muhammad Ali had the last contest of a professional boxing career that went on far too long 40 years ago this December; a sad points defeat to Trevor Berbick.

This article is part of our ICONS series. Written by Alex Reid as part of our IMAGO Zine Issue #2 here

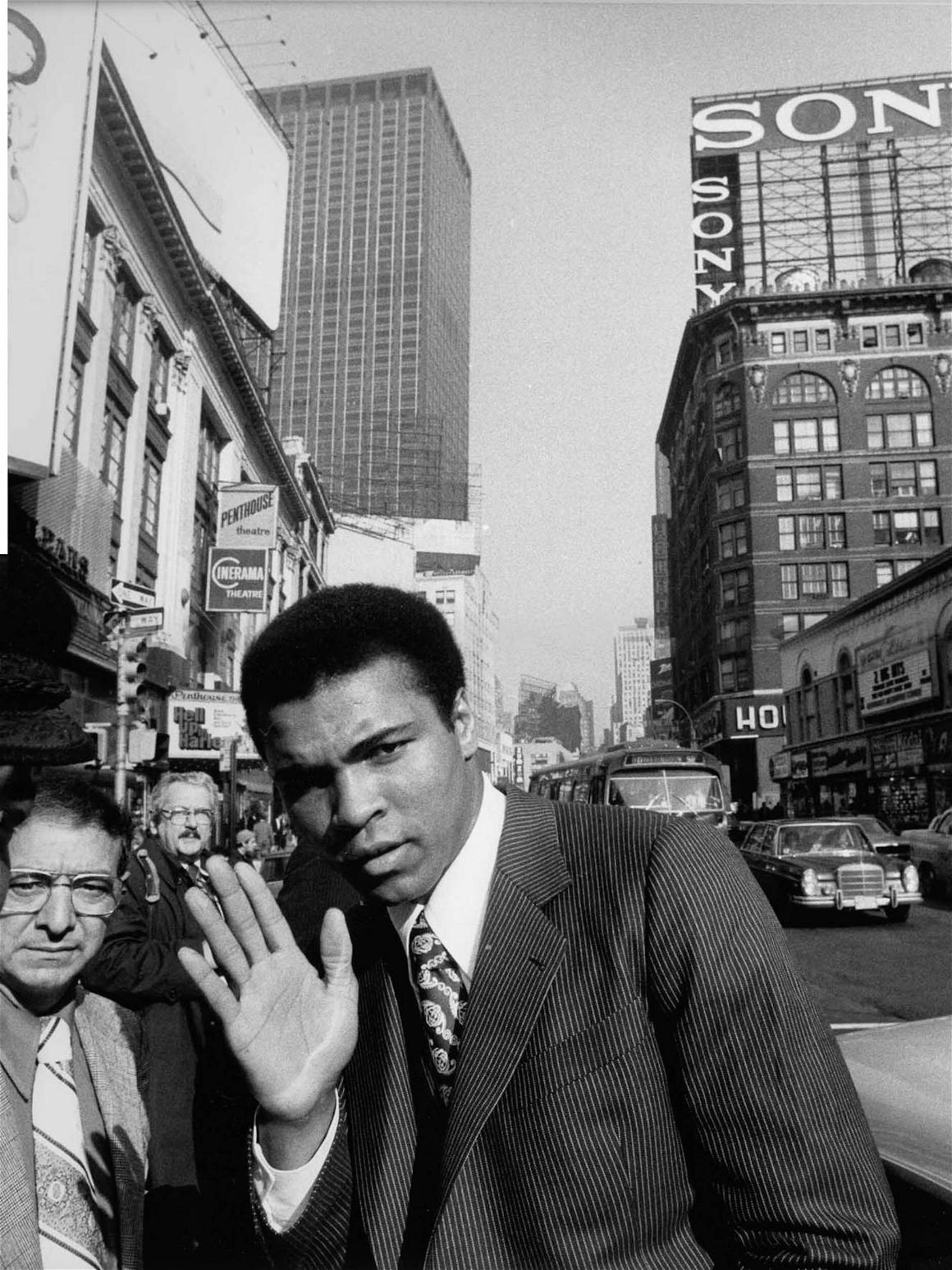

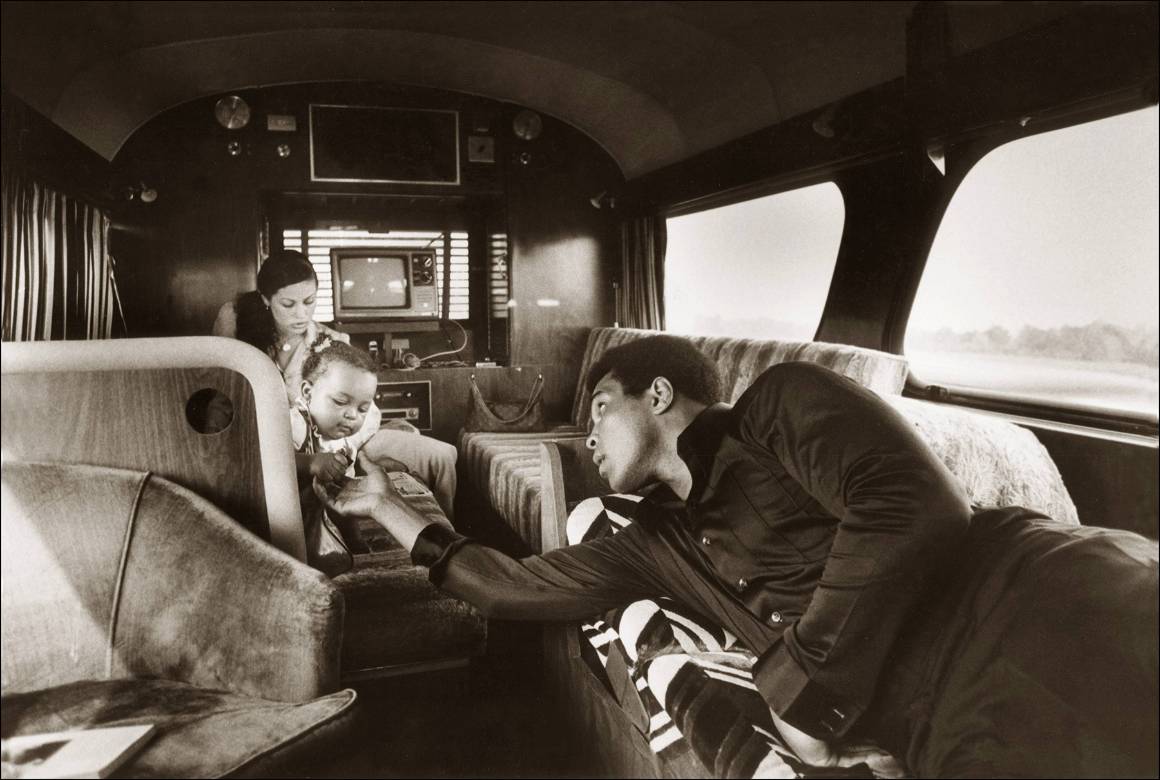

So any modern athlete now who references Ali as their idol, any budding sports fan under 40 who has a poster of Ali on their wall and calls him a hero, can have no memory of Ali as an active fighter. Or indeed, as a social presence, as the Parkinsonism that afflicted him from the mid-1980s onwards did what no in-ring opponent could do and finally shut that eloquent mouth.

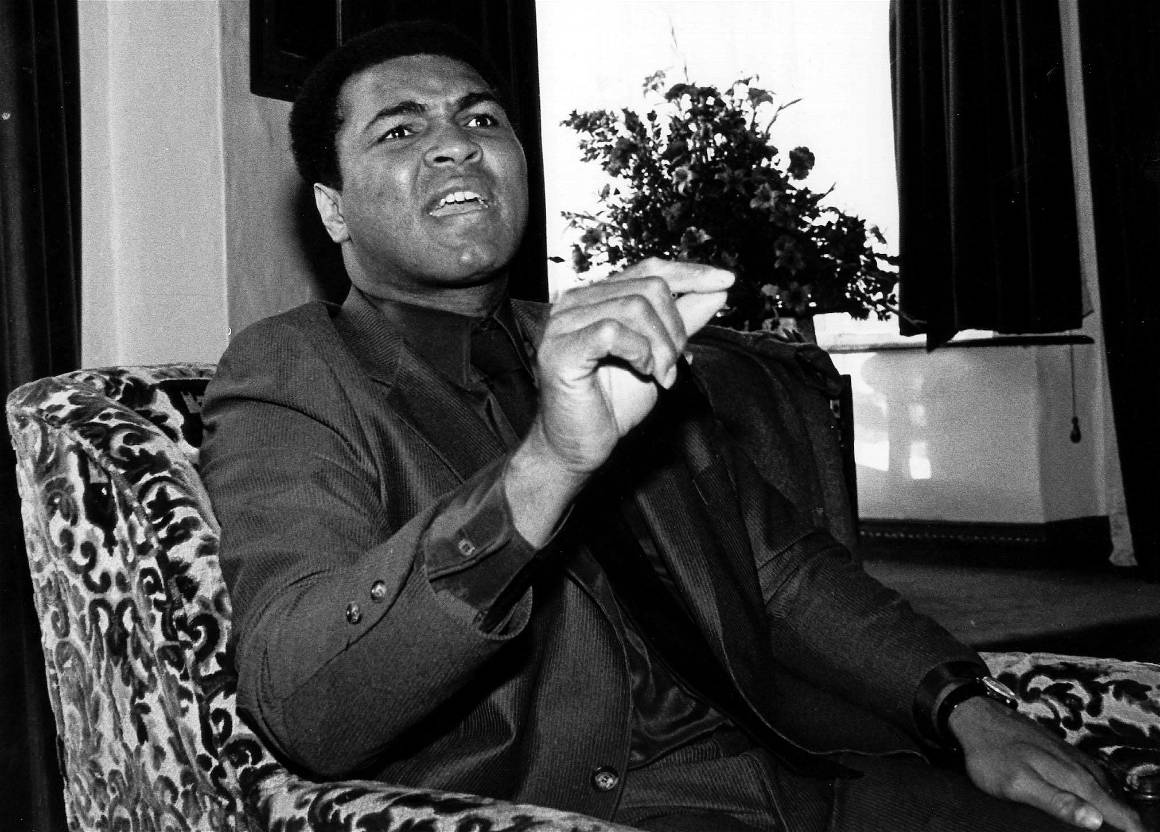

“My big concern today is that Ali is famous simply for being famous,” says Thomas Hauser – Ali’s official biographer and close friend until his death in June 2016 – speaking on the phone from New York.

“People know that he stood up for his principles, but they really don’t know what his principles were. Really, to fully appreciate what he meant, you almost had to live through his times – and every day pick up the newspaper to find something about this man.”

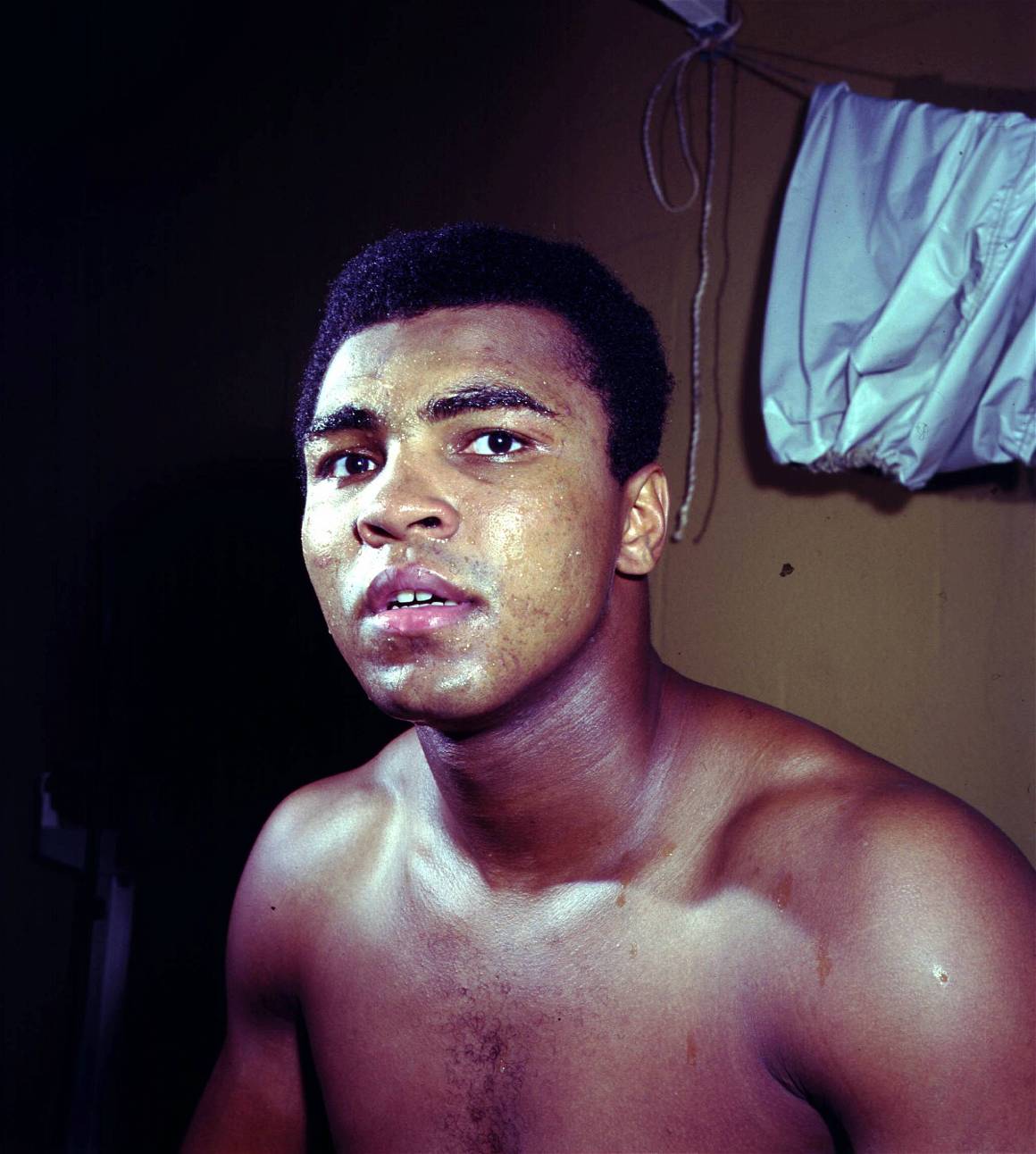

Ali’s legacy has been ironed out into a catchy quote on an Instagram post, a 10-second video clip of him dodging punches with his hands by his waist, an iconic image of one of the world’s most handsome athletes framed on a bedroom wall. The complexity of who he really was, what he achieved – his shortcomings as well as his glories – fading in the rearview mirror.

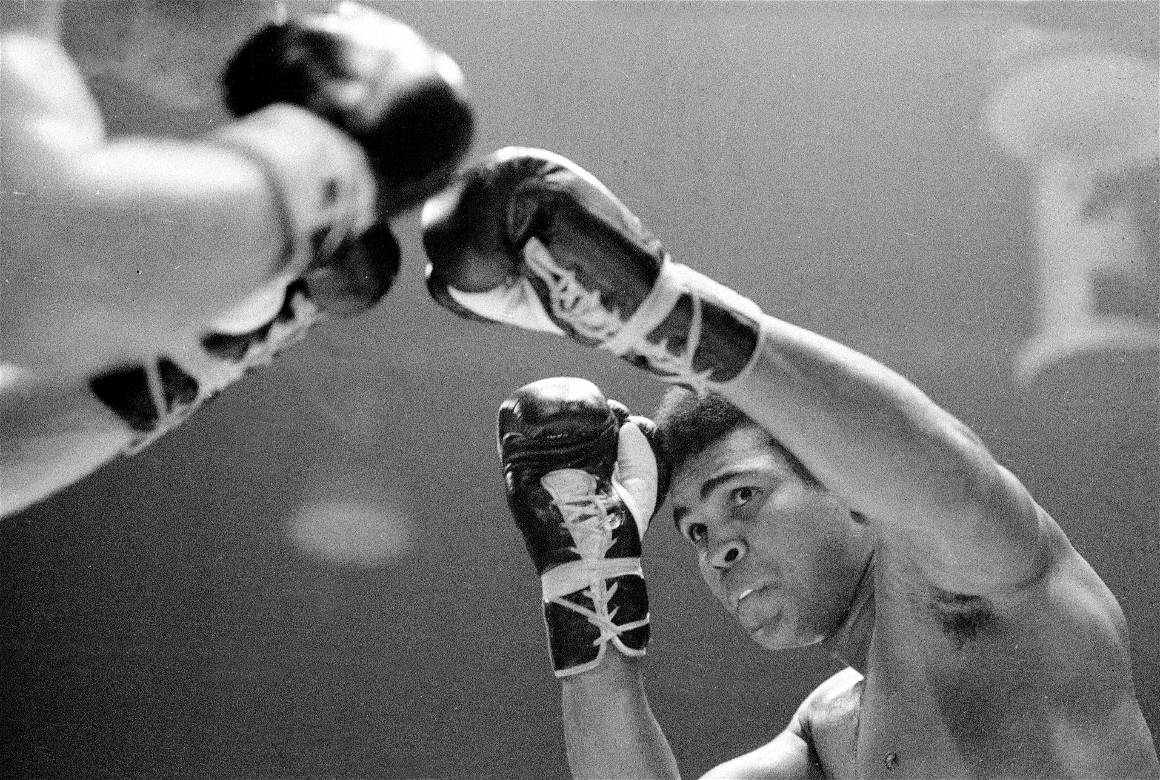

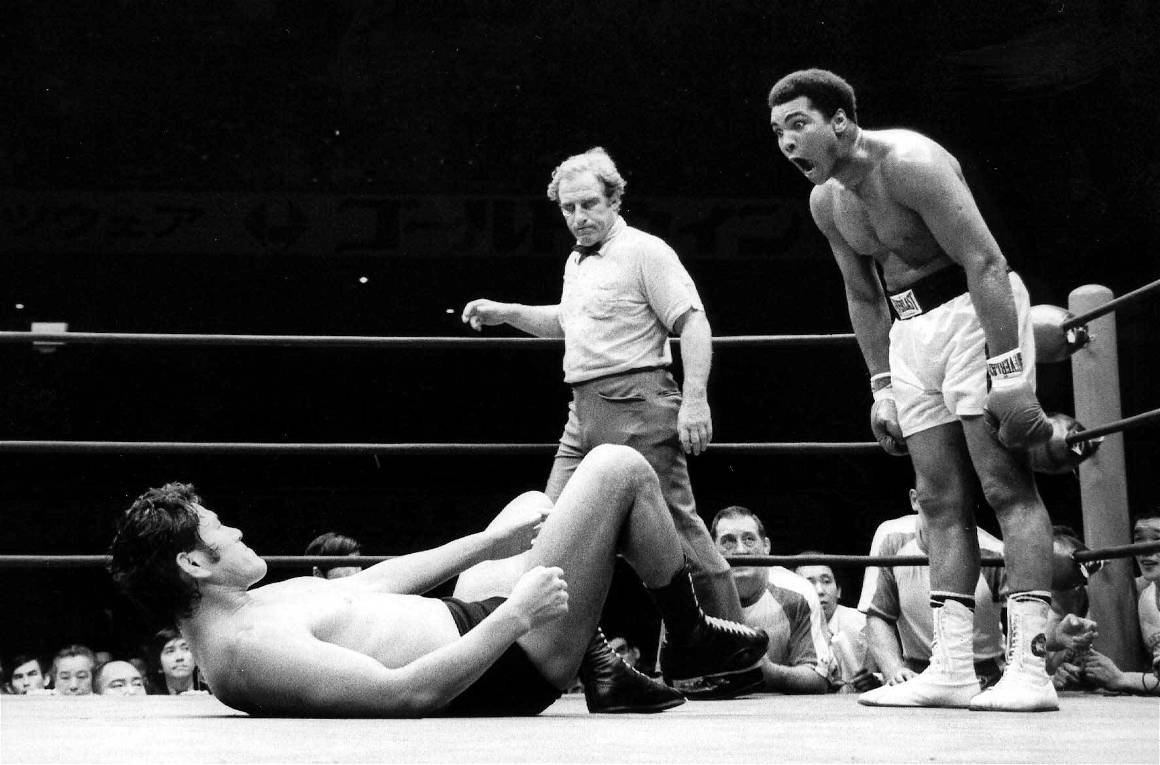

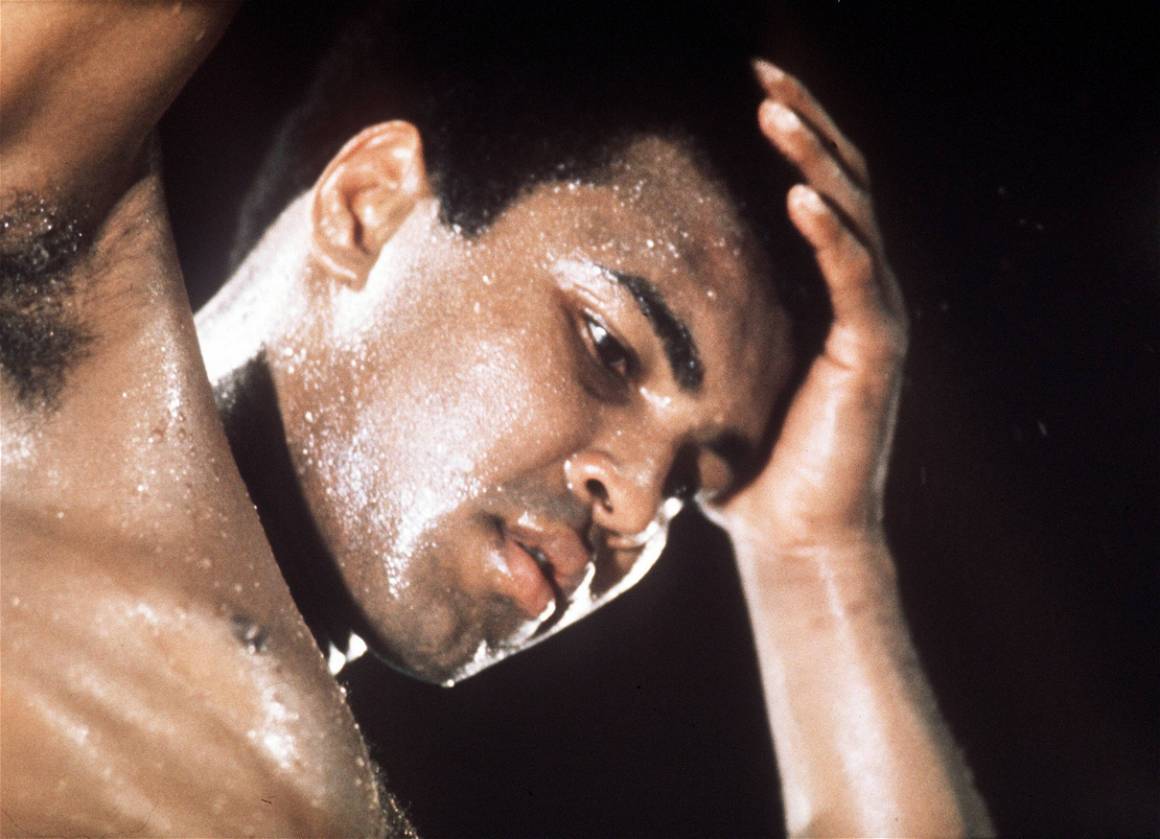

The three-time world heavyweight champion’s genius in the ring is there to be uncovered for those who watch the fights. The astonishing grace of a 6ft 3in, 200lb+ fighter moving like a ballet dancer in his prime, then the audacious bravery of his later fights when his reflexes slowed but his tremendous will and boxing brain carried him to victories over younger men.

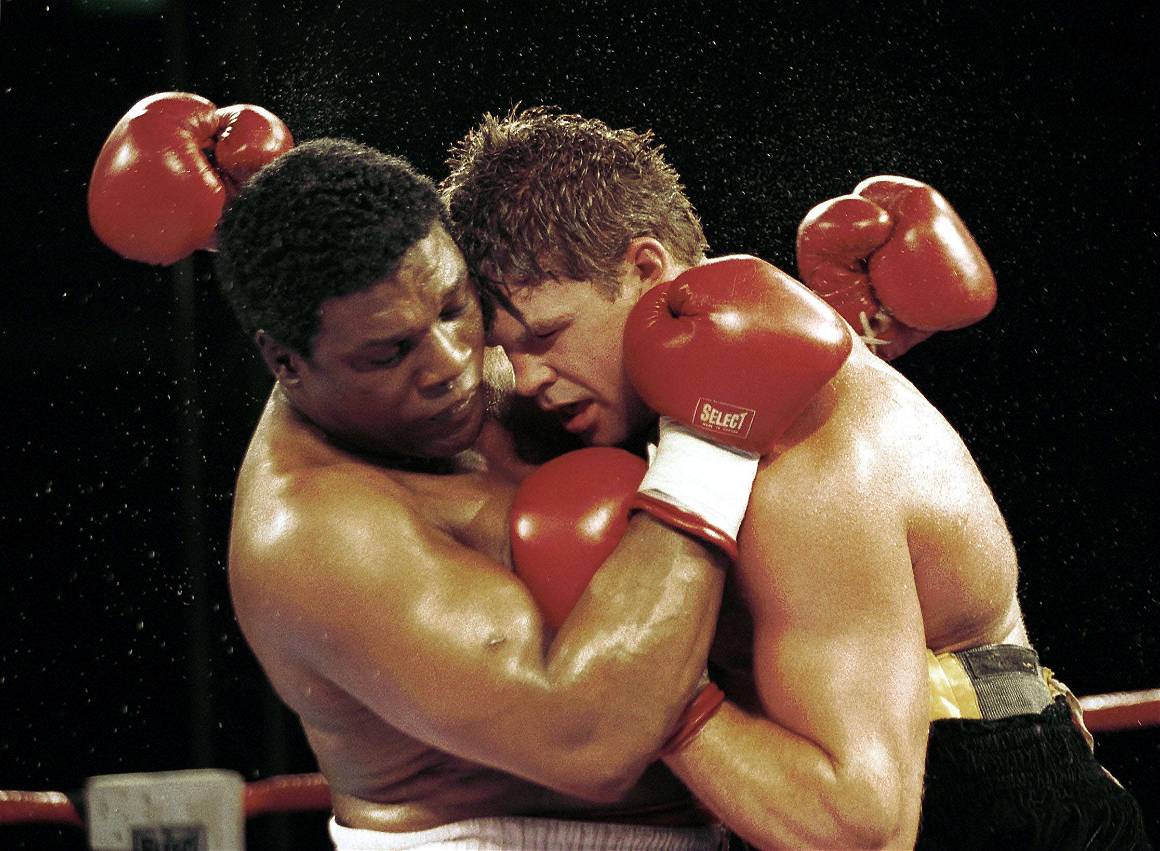

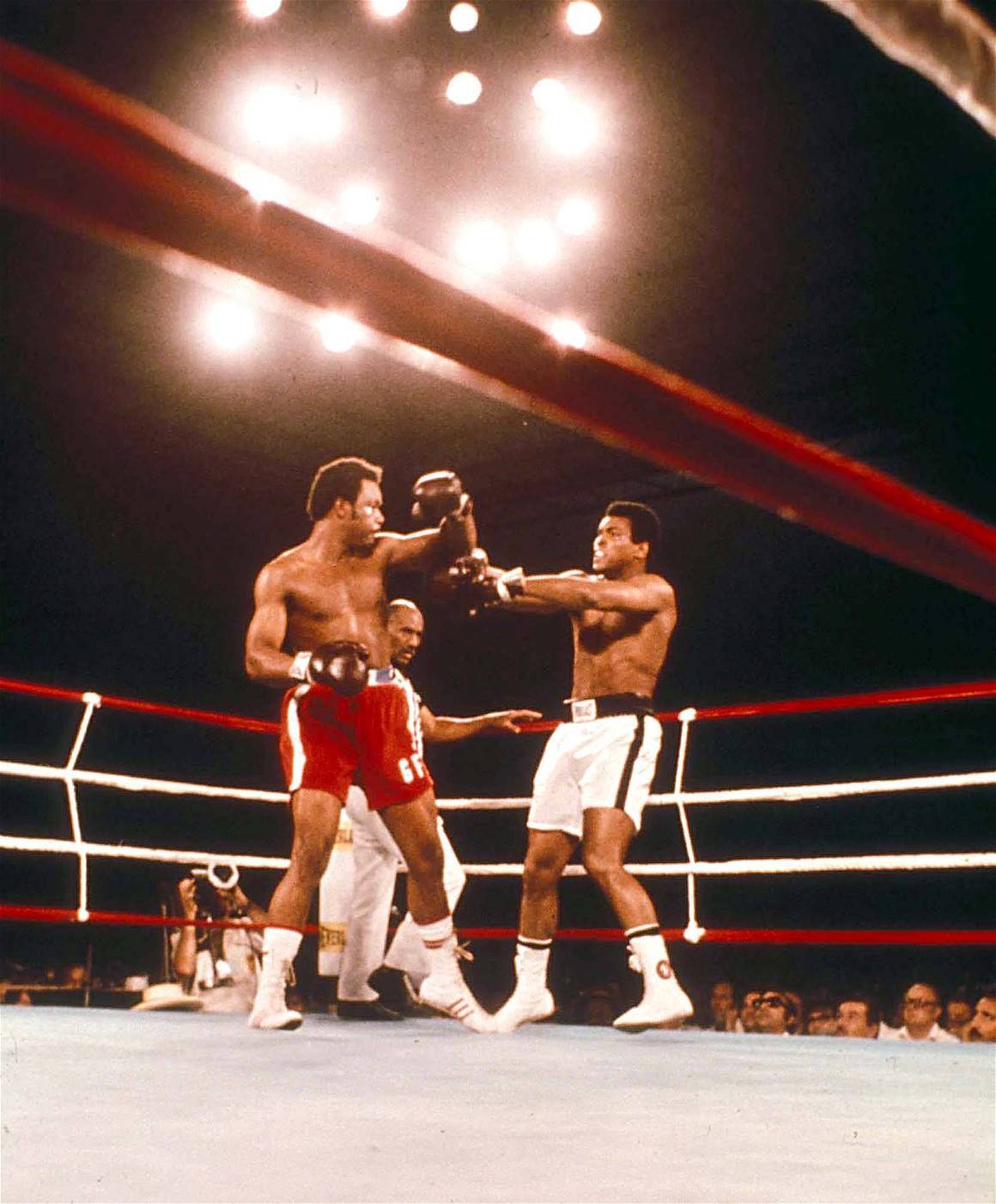

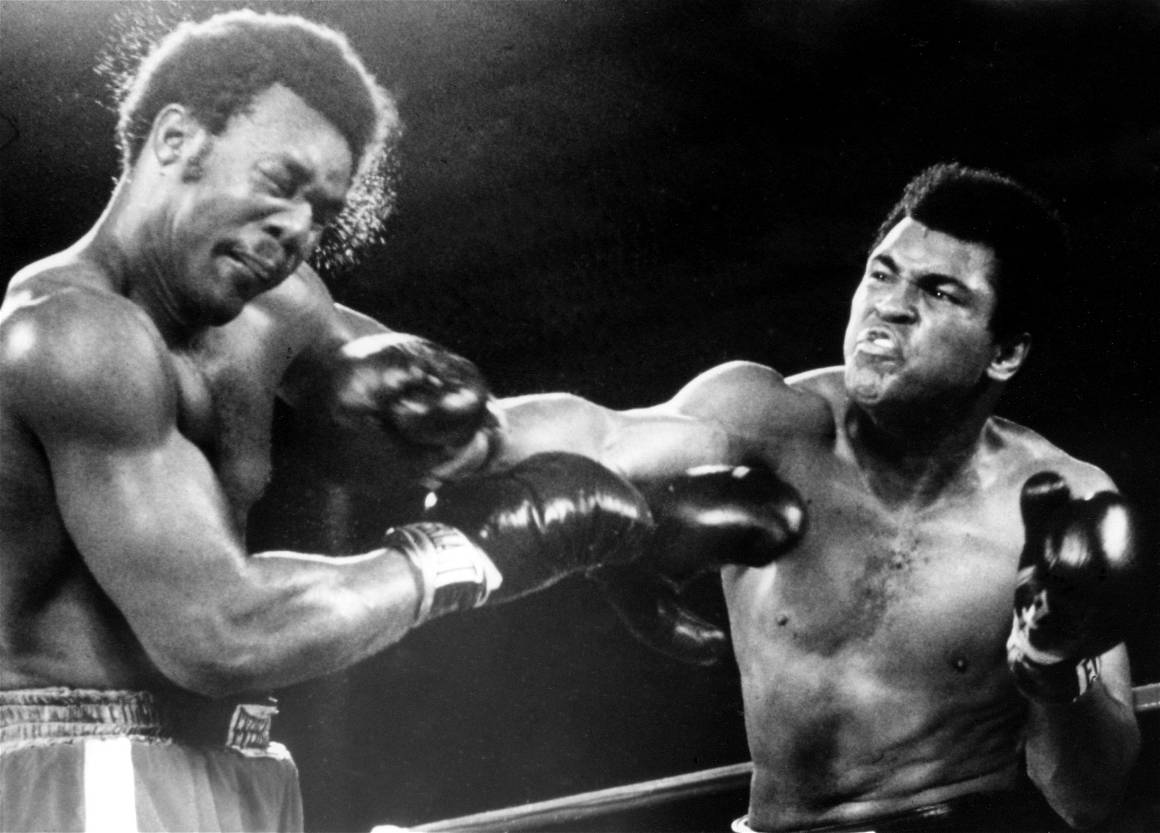

However even Ali’s most legendary win, perhaps the most famous fight of all time, is largely misrepresented.

Ali’s dethroning of the seemingly invincible George Foreman in Zaire in 1974, AKA ‘The Rumble in the Jungle’, is known as the rope-a-dope fight. The one where Ali absorbed hellacious punishment, allowing the 25-year-old Foreman to punch himself out, before coming back to batter his weary foe to the canvas. At best a simplification, at worst an outright illusion. Watch the fight and Ali does retreat to the ropes, but also jolts Foreman’s head back with right-hand leads in the first round, blocks incoming blows with his elbows and beats Foreman with cunning as well as courage. By the time of his eighth-round KO, Foreman is a spent force – behind on points and losing badly – but because of the shots he has taken rather than those he has depleted himself throwing.

If even Ali’s most memorable victory is misconstrued, no wonder his social legacy is nowhere near understood. Frankly, some of the beliefs that Ali held during the early years of his career would shock many who consider him an idol.

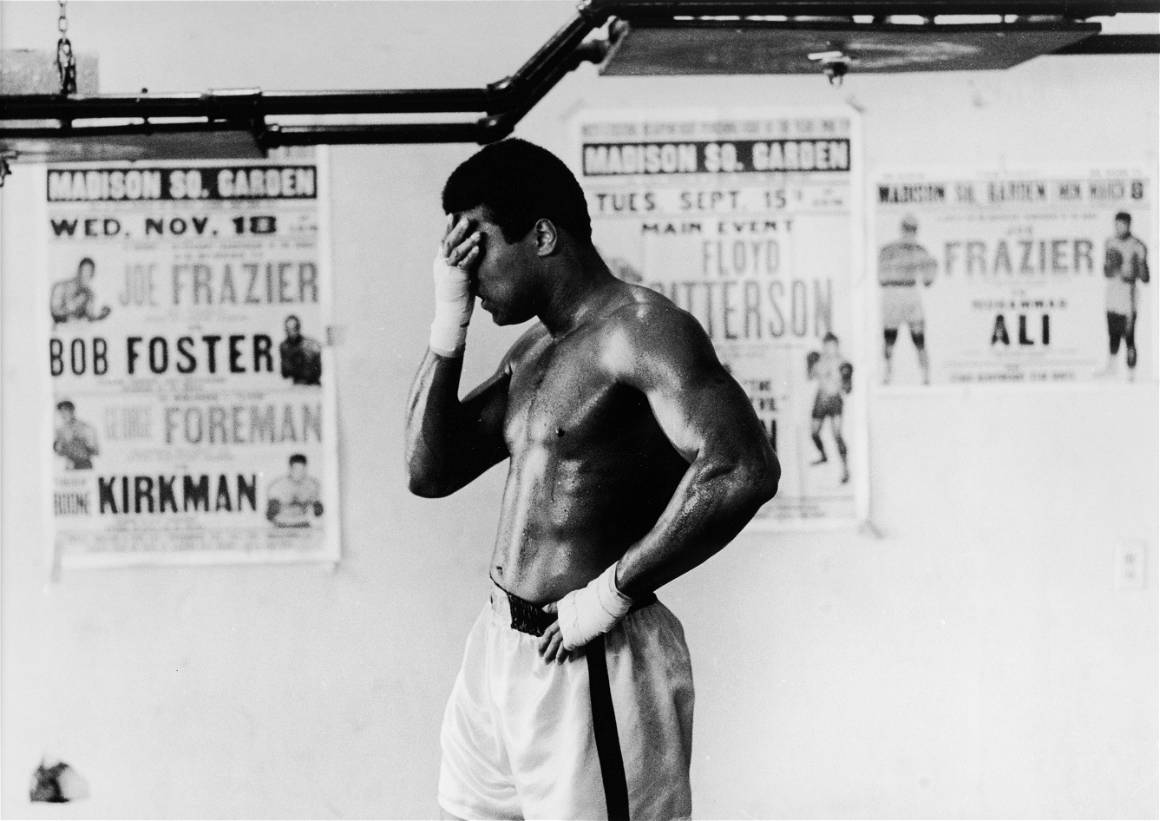

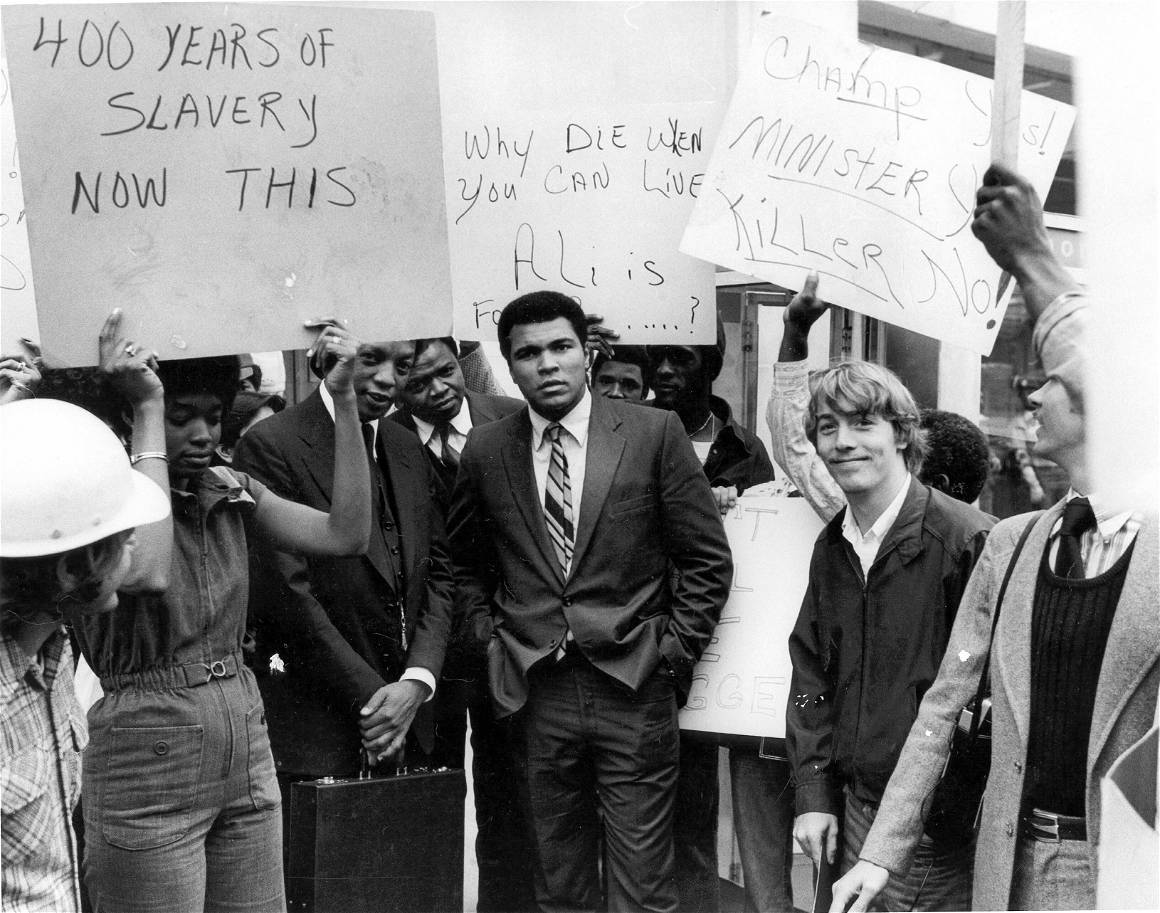

Ali was a conscientious objector to the war in Vietnam in 1967, a principled stance that cost him financial and sporting success. It led to him being stripped of his world heavyweight championship at age 25 and a three-and-a-half year exile from boxing.

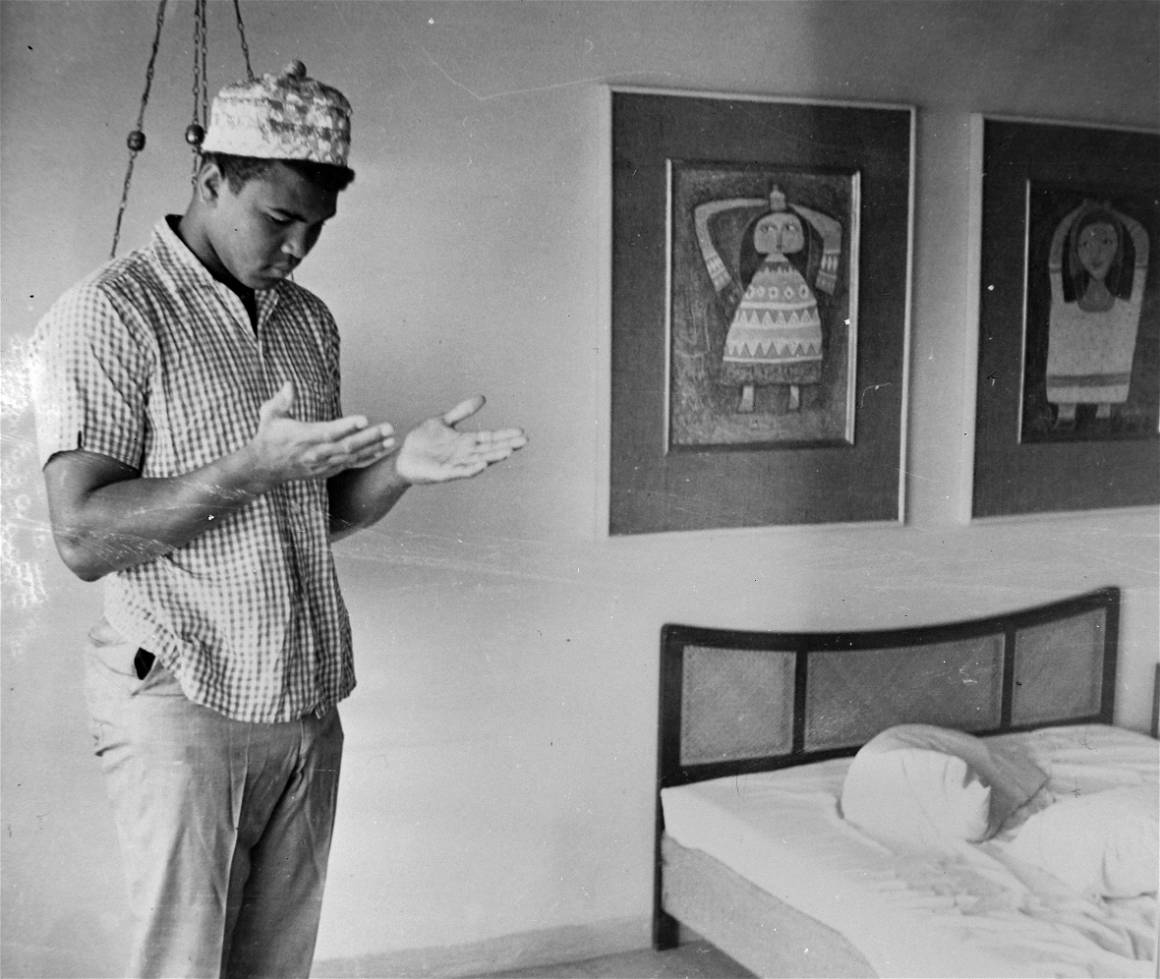

Eventually, it also brought Ali widespread popularity as, even in the US, public opinion slowly turned against the war. In the 1960s, however, Ali belonged to the Nation of Islam, which as Hauser explains, “is very different from orthodox Islam. It’s a form of American apartheid, where they preached that the white people were devils.”

The Nation also taught that the white devil-race was created by a scientist, Mr Yakub, 6,600 years ago – and that man-made UFOs circled the earth that would one day bomb the world. These were the views that a straight-faced Ali willingly espoused to large crowds and into the microphones of eager journalists.

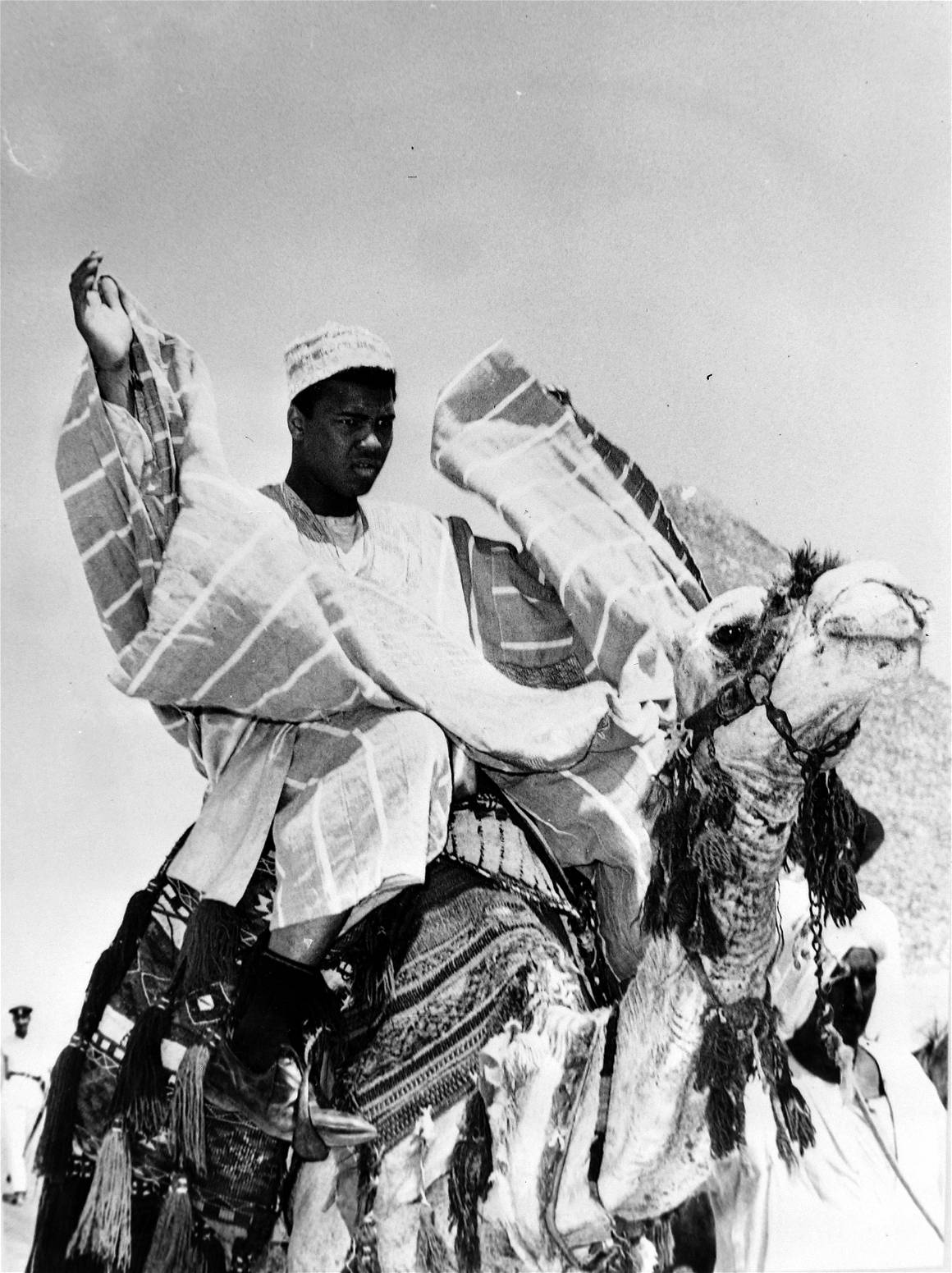

Over time, his views changed. He became an orthodox Muslim and someone who embraced people of all races and faiths. But the fact remains that, for a period at the peak of his career, his stated beliefs make uncomfortable reading on paper – even if they are the understandable result of growing up in Louisville, Kentucky, at a time when racial discrimination was the norm.

The details of Ali’s beliefs, however, were less impactful than the fact that he was willing to stand up to US authorities, to make himself heard. Even the famed boasting had an impact beyond what was first apparent. As Hauser explains: “Every time Ali said ‘I’m so pretty’, what he was really saying – before it became fashionable – was ‘black is beautiful’. He became a beacon of hope not just for black people, but for oppressed people all over the world.”

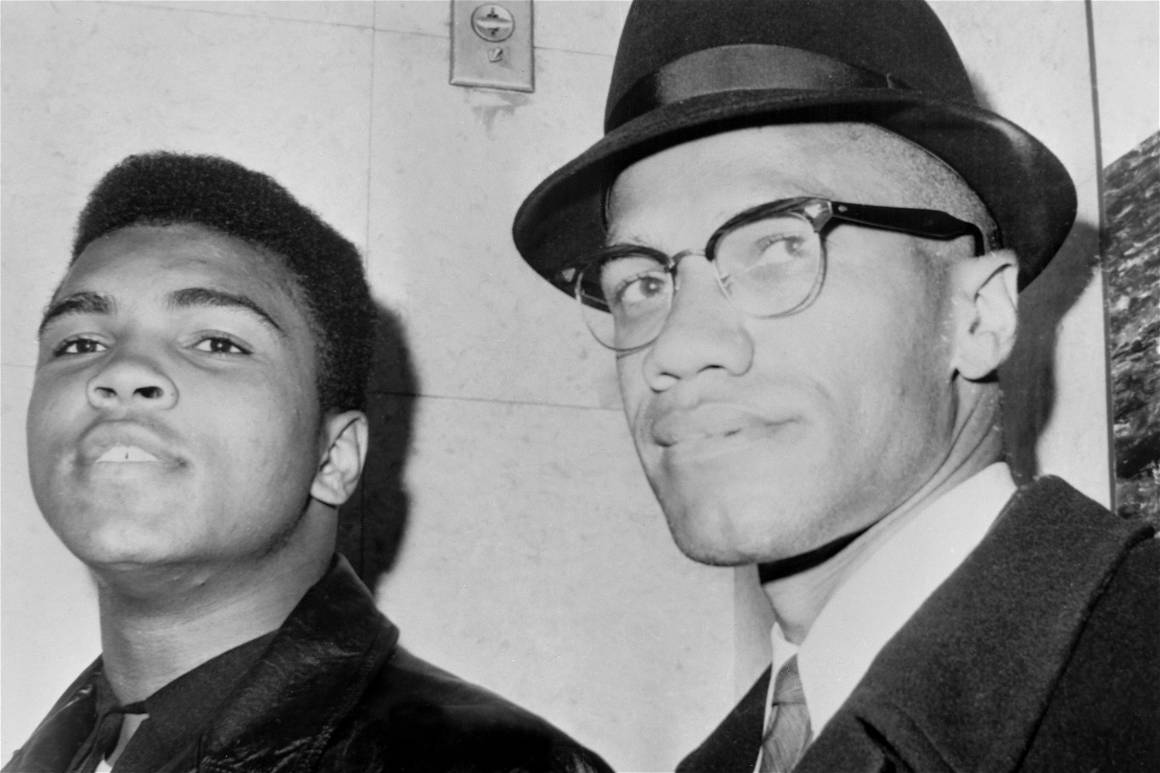

Still, Ali took a more militant, segregationist stance than other black civil rights figures, such as Martin Luther King. He also turned his back on his friend Malcolm X after the latter split from the Nation of Islam. Ali would later call it: “One of the mistakes that I regret most in my life.”

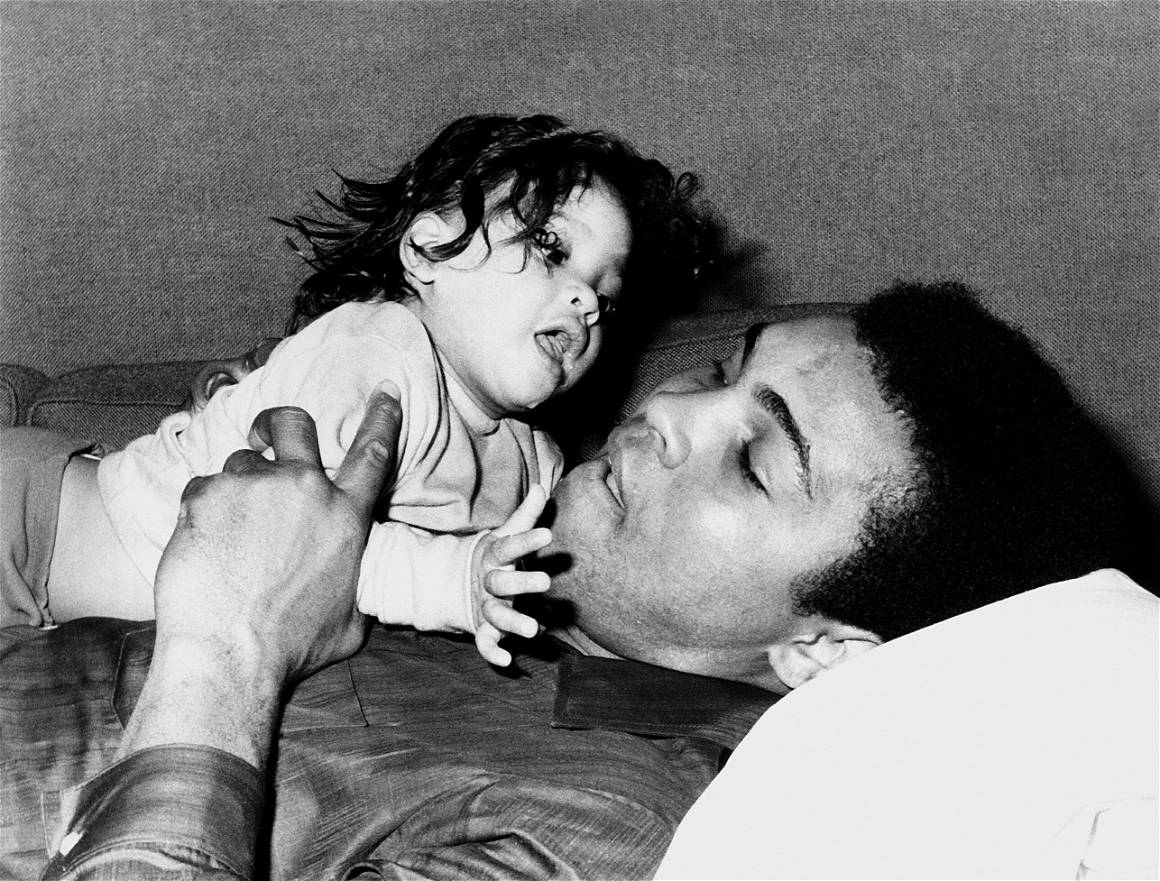

But it is the human side of Ali, the fact that he espoused views he’d later come to regret, his errors and missteps, that help us to understand the man behind the myth. Ali could be charming, gracious, kind and brave. But he could also be cruel, contradictory, selfish and obstinate. These defects don’t ruin the legend, they embellish it. The fact that he overcame so much, including his own mistakes, to become that beacon of global hope makes his story all the more stirring. Assuming people take the time to learn it.

But then maybe Ali, the alpha and the omega of his sport, is part responsible for this simplification of his legend. In 1964, training for his first world title fight against Sonny Liston, the then 22-year-old Cassius Clay told reporters simply: “I’m the greatest thing that ever lived.”

It was another crazy line from the brash underdog. But his self-christened nickname of ‘The Greatest’ stuck with Ali, as he began to prove it inside and outside the ring. He remains ‘The Greatest’ now, even if it’s to a generation that has no real idea what he went through to deserve that epitaph.