Women in Iran could not enter football stadiums for decades – but recently, the government claims that changes are slowly underway. Iranian guest writer Fatemeh Roshan shares a personal account of growing up in this reality.

After Decades, Are Stadiums Opening Up to Women in Iran?

Just last month, women in the capital of Iran could watch their favourite football teams from inside the Azadi Stadium, which in Persian means freedom stadium, for the first time in over 40 years. As an Iranian woman who had lived her entire life under the unwritten rule that we are not allowed to enter stadiums, I could not believe this discriminatory rule was abolished when I received the news from home.

My confusion may seem strange initially, but it has been a part of our lives for several decades.

In 2019, FIFA put pressure on Iranian authorities to allow women into stadiums, but there have been restrictions on which matches they can attend, where they can sit, and how many are allowed in the stadium. Women were blocked in March of 2022 from watching a match against Lebanon, but were recently allowed to attend a match from Iran’s domestic championship on August 25.

For the past several years and since the 1979 Islamic revolution, Iranian women have faced the consequences of prison and harassment if they attempted to enter a stadium. One of us even died – Sahar Khodayari committed suicide by setting herself on fire in front of a court that sentenced her to two years of prison just for trying to enter a stadium.

The following essay is a personal account of my first experience attending a stadium outside my home country when I visited Barcelona in November of 2021, writing as a female journalist reporting in some parts, and as an Iranian woman in others.

The difference between what I am used to and the new situation has been splitting in my mind as I try to regather by bringing back old memories, contrasting life and tragedy.

See IMAGO’s collection on Iranian women in stadiums.

First Game

by Fatemeh Roshan.

19:30, November 20, Barcelona

The red lights illuminate the smoke around us amidst singing, dancing, and cheering. The red-blue flags are twirling in the air.

Un dia de partit, al Gol Nord vaig anar. *It was matchday, I went to the ‘Gol Nord’ stadium.*

But what should I do?” I ask myself. “Am I one of them?” Suddenly, everything gets hectic. “Move on, what are you doing?” my friend asks me. People keep moving around. They’re trying to make space in the middle and open up more space, like a tunnel. A bus is hardly visible in the back. Flags go up and fly in the air. The lights turn on. The air goes red; soldiers are getting ready. “Alé alé alé alé alé alé alé alé.”

November 2018, Tehran. The Stadium of 100,000 Boys

Today is the final game of the AFC Champions League in Tehran in the Azadi Stadium, or ‘Freedom Stadium,’ where women are usually not allowed to enter, only men. We used to call it “the stadium of 100,000 boys.”

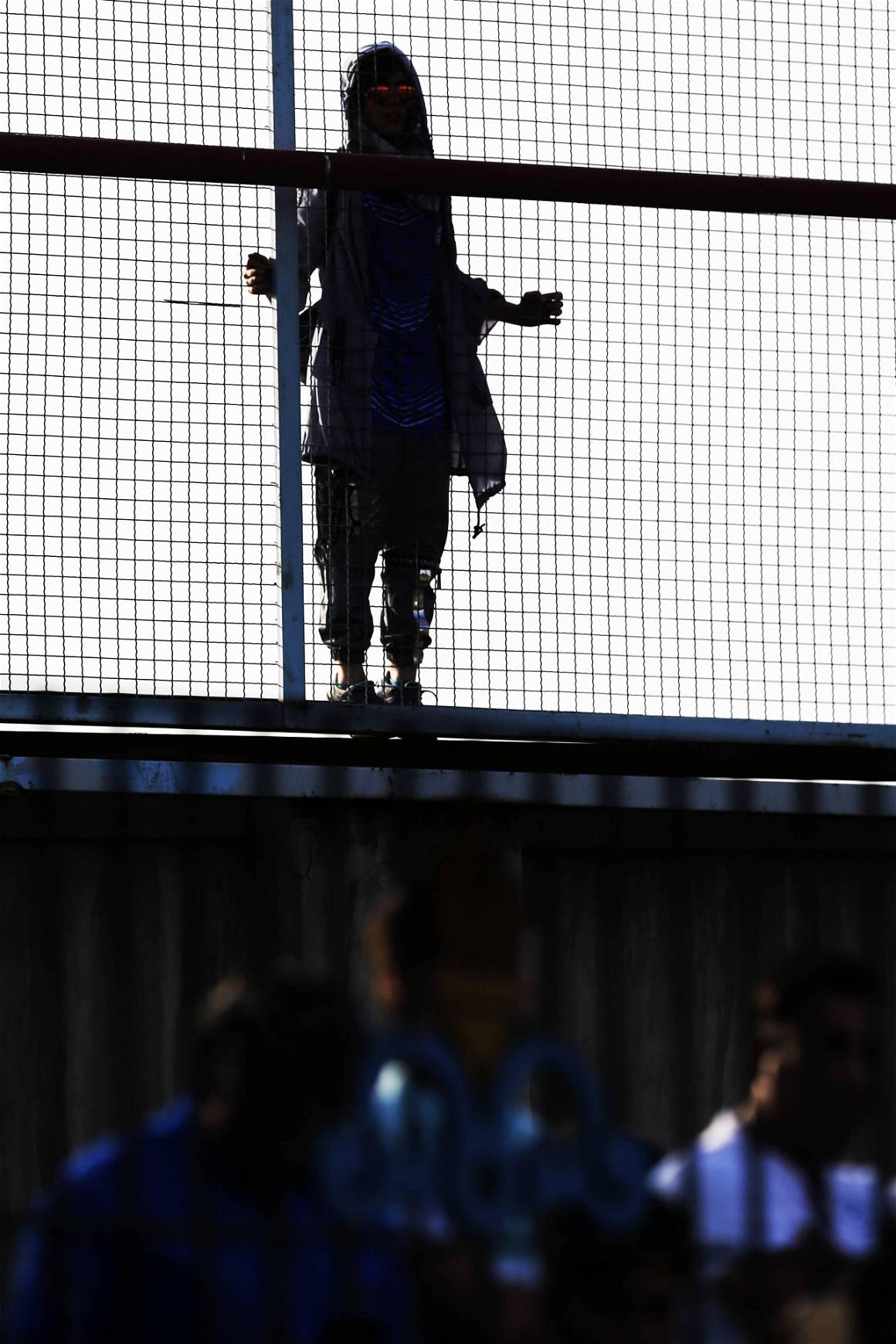

But for today, because of pressure from FIFA and to avoid consequences, they decided to let some women go inside. Not for real, of course, just a few carefully selected women.

They probably don’t want this to be normalized. I’m watching the game on TV; my female friends went to the stadium. They are coming back, one of them was crying on the phone, she couldn’t go inside. Even though they had the tickets, men were the priority.

19:45, November 20, Barcelona

We must walk around to the gate. Fans are singing on the way. The number of people who are offering unofficial tickets is rising; we are getting closer. Gate 19; I see the stadium at the end of the street, but this is not my first time seeing one, just my first time being invited in. A man is the security check-in for our gate. He asks for my ticket and kindly says, “enjoy the game.”

September 2019, Tehran. The Blue Girl

I start my day by reading the news about a girl. She attempted suicide in front of a court in Tehran. The court told her she might go to jail for six months to two years, as she had already been arrested in March for trying to enter a stadium while dressed up as a man and the security men caught her. She was jailed for a few days and now was facing longer jail time once again. She set herself on fire. She is dead, and people already gave her a name: ‘Blue Girl.’

19:55, November 20, Barcelona

Només entrar a la grada, em vaig enamorar. *I just entered the tribune, and I fell in love.*

People are singing. I want to sing too, but I don’t know what it means. We walk uphill. Our entrance is number 434, but I don’t know what the differences between the sections are. For me, it is a number that gives me something that I have never seen. I can see the entrance. Walking to the stairs, I see the light from inside. For a few seconds, I can’t hear. Should I go up?

June 2016, Tehran. Empty Stadium

“Wait! Stop there!” I turn to the security man who is running to me and shouting. “What’s wrong?” I ask. “Boss said he changed his mind; you can’t get in. It is forbidden”.

I just finished my interview with the head of Shiroudi Stadium. I want to write a report on an old monument located inside. The stadium is empty. We start arguing. Doesn’t work, as always. The cameraman goes inside to take pictures. I walk down the entrance stairs.

20:30, November 20, Barcelona

El cor em bategava, no em preguntis per què. * My heart was beating, don’t ask me why.*

For a few seconds, I can’t breathe. It is enormous, different from my imagination. I ask my friend to take my hand: “Have you ever seen somebody fall from above?” He laughs. He takes it as a joke, I wasn’t joking.

A man with three children sits next to us. Two of them are there for the first time like me. Youngest is around five, and the oldest ten. The man is teaching them how to behave. I try to listen, but I can’t hear; I try to look carefully. Does he know that now he is actually teaching four children?

May 2017, Tehran. Presidential Election

We will die here. It is the first time that I have been here. In the Azadi stadium with my colleagues, it is too warm and crowded; we are sitting in the middle. Hassan Rohani is speaking for his presidential election. People are happily screaming after his words. I am trying to listen and write; Rohani repeats something that he said four years ago in his election campaign, perhaps an empty promise:

“I will demand that women have access to the stadium, as men, why not? Is that a real problem?”

21:30, November 20, Barcelona

Fans react to every movement of FC Barcelona’s players. If Españyol gains a single opportunity, they lose it fast because of fans’ screams. It is crazy to me how vital fans are in a game. I always heard it, now I see it – and it’s unbelievable. I try to scream too; do they realize what I am saying in Persian? I hope someone is around who understands.

November 20, Barcelona, 22:00. Hate or Love

I take some pictures for my Instagram. I am smiling in the photo and look so happy. Opening the app, should I post it? What do others think about me? That she went to another country and wanted to show us something that we can’t do? What will Mahtab think about me? She hates football. Once, she told me that her hate for football came from her childhood. When she asked her brother to take her to the stadium, he was always elusive and had no explanation. When she asked someone else, she realized it is forbidden for a girl to go inside a stadium. She started to hate football and never talked about it to her brother again. I closed the app.

November 20, Barcelona,23:00. Camp Nou

“Alé alé alé alé alé alé alé alé alé alé alé alé” *I sing this one perfectly with the family next to us.* The woman asks, how much of a fan are you? What should I say? I was never a fan of Barça, but what about now? The game is almost finished. We must leave. I try to sing with people:

Del Barça sóc ‘supporter’, sempre t’animaré. *I am a fan of Barça, I will always support you.*

This article is dedicated to Sahar Khodayari, ‘Blue Girl.’